Faster integer formatting - James Anhalt (jeaiii)’s algorithm

Published:

This post is about an ingenious algorithm for printing integers into decimal strings. It sounds like an extremely simple problem, but it is in fact quite more complicated than one might imagine. Let us more precisely define what we want to do: we take an integer of specific bit-width and a byte buffer, and convert the input integer into a string consisting of its decimal digits, and then write it into the given buffer. For simplicity, we will assume that the integer is unsigned and is of $32$-bits. So, we want to implement the following function written in C++:

char* itoa(std::uint32_t n, char* buffer) {

// Convert n into decimal digit string and write it into buffer.

// Returns the position right next to the last character written.

}

There are numerous algorithms for doing this, and I will dig into a clever algorithm invented by James Anhalt (jeaiii), which seems to be the fastest known algorithm at the point of writing this post.

Disclaimer

I actually have not looked (and will not look) carefully at his code (MACROS, oh my god 😱) and have no idea what precisely was the method of analysis he had in mind. All I write here is purely my own analysis inspired by reading these lines of comment he wrote:

// 1. form a 7.32 bit fixed point numner: t = u * 2^32 / 10^log10(u)

// 2. convert 2 digits at a time [00, 99] by lookup from the integer portion of the fixed point number (the upper 32 bits)

// 3. multiply the fractional part (the lower 32 bits) by 100 and repeat until 1 or 0 digits left

// 4. if 1 digit left mulptipy by 10 and convert it (add '0')

//

// N == log10(u)

// finding N by binary search for a 32bit number N = [0, 9]

// this is fast and selected such 1 & 2 digit numbers are faster (2 branches) than long numbers (4 branches) for the 10 cases

//

// /\____________

// / \______ \______

// /\ \ \ \ \

// 0 1 /\ /\ /\ /\

// 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

So it is totally possible that in fact what’s written in this post has nothing to do with what he actually did; however, I strongly believe that what I ended up with is more or less equivalent to what his code is doing, modulo some small minor differences.

Naïve implementations

The very first problem that anyone who tries to implement such a function will face is that we want to write digits from left to right, but naturally we compute the digits from right to left. Hence, unless we know the number of decimal digits in the input upfront, we do not know the exact position in the buffer that we can write our digits into. There are several different strategies to cope with this issue. Probably the simplest (and quite effective) one is to just print the digit from right to left but into a temporary buffer, and after we get all digits of $n$ we copy the temporary buffer back to the destination buffer. At the point of obtaining the left-most decimal digit of $n$, we also get the length of the string, so we know what exact bytes to copy.

With this strategy, we can think of the following implementation:

char* itoa_naive(std::uint32_t n, char* buffer) {

char temp[10];

char* ptr = temp + sizeof(temp) - 1;

while (n >= 10) {

*ptr = char('0' + (n % 10));

n /= 10;

--ptr;

}

*ptr = char('0' + n);

auto length = temp + sizeof(temp) - ptr;

std::memcpy(buffer, ptr, length);

return buffer + length;

}

(Demo: https://godbolt.org/z/7G7ecs7r4)

The size of the temporary buffer is set to $10$, because that’s the maximum possible decimal length for std::uint32_t.

The mismatch between the order of computation and the order of desired output is indeed a quite nasty problem, but let us forget about this issue for a while because there is something more interesting to say here.

There are several performance issues in this code, and one of them is the division by $10$. Of course, since the divisor is a known constant, our lovely compiler will automatically convert the division into multiply-and-shift (see this classic paper for example), so we do not need to worry about the dreaded idiv instruction which is extremely infamous of its performance. However, for simple enough algorithms like this, multiplication can still be a performance killer, so it is reasonable to expect that we will get a better performance by reducing the number of multiplications.

Regarding this, Andrei Alexandrescu popularized the idea of generating two digits per a division, so halving the required number of multiplications. That is, we first prepare a lookup table for converting $2$-digit integers into strings. Then in the loop we perform divisions by $100$, rather than $10$, to get $2$ digits per each division. The following code illustrates this:

static constexpr char radix_100_table[] = {

'0', '0', '0', '1', '0', '2', '0', '3', '0', '4',

'0', '5', '0', '6', '0', '7', '0', '8', '0', '9',

'1', '0', '1', '1', '1', '2', '1', '3', '1', '4',

'1', '5', '1', '6', '1', '7', '1', '8', '1', '9',

'2', '0', '2', '1', '2', '2', '2', '3', '2', '4',

'2', '5', '2', '6', '2', '7', '2', '8', '2', '9',

'3', '0', '3', '1', '3', '2', '3', '3', '3', '4',

'3', '5', '3', '6', '3', '7', '3', '8', '3', '9',

'4', '0', '4', '1', '4', '2', '4', '3', '4', '4',

'4', '5', '4', '6', '4', '7', '4', '8', '4', '9',

'5', '0', '5', '1', '5', '2', '5', '3', '5', '4',

'5', '5', '5', '6', '5', '7', '5', '8', '5', '9',

'6', '0', '6', '1', '6', '2', '6', '3', '6', '4',

'6', '5', '6', '6', '6', '7', '6', '8', '6', '9',

'7', '0', '7', '1', '7', '2', '7', '3', '7', '4',

'7', '5', '7', '6', '7', '7', '7', '8', '7', '9',

'8', '0', '8', '1', '8', '2', '8', '3', '8', '4',

'8', '5', '8', '6', '8', '7', '8', '8', '8', '9',

'9', '0', '9', '1', '9', '2', '9', '3', '9', '4',

'9', '5', '9', '6', '9', '7', '9', '8', '9', '9'

};

char* itoa_two_digits_per_div(std::uint32_t n, char* buffer) {

char temp[8];

char* ptr = temp + sizeof(temp);

while (n >= 100) {

ptr -= 2;

std::memcpy(ptr, radix_100_table + (n % 100) * 2, 2);

n /= 100;

}

if (n >= 10) {

std::memcpy(buffer, radix_100_table + n * 2, 2);

buffer += 2;

}

else {

buffer[0] = char('0' + n);

buffer += 1;

}

auto remaining_length = temp + sizeof(temp) - ptr;

std::memcpy(buffer, ptr, remaining_length);

return buffer + remaining_length;

}

(Demo: https://godbolt.org/z/vnMTf7s9r)

The core idea of James Anhalt’s algorithm

So, with the above trick of grouping $2$ digits, how many multiplications do we need for integers of, say, $10$ decimal digits? Note that we need to compute both the quotient and the remainder, and as far as I know at least $2$ multiplications should be performed to get both of them and there is no way to do it with just one multiplication. Hence, for each pair of $2$ digits, we need to perform $2$ multiplications, thus for integers with $10$ digits we need $8$ multiplications, since we need $4$ divisions to separate $5$ pairs of $2$ digits.

Quite surprisingly, in fact we can almost halve that number again into $5$, which (I believe) is the core benefit of James Anhalt’s algorithm. The crux of the idea can be summarized as follows: given $n$, we find an integer $y$ satisfying

\[n = \left\lfloor\frac{10^{k}y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor\]for some nonnegative integer constants $k$ and $D$.

This transformation is a real deal, because after we get such $y$, we can extract $2$ digits of $n$ per a multiplication. To see how, recall that in general

\[\left\lfloor\frac{a}{bc}\right\rfloor =\left\lfloor\frac{\lfloor a/b \rfloor}{c}\right\rfloor\]holds for any positive integers $a,b,c$; that is, dividing $a$ by $bc$ is equivalent to dividing $a$ by $b$ first and then by $c$. Therefore, for any $l\leq k$, we have

\[\left\lfloor\frac{10^{k-l}y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor = \left\lfloor\frac{n}{10^{l}}\right\rfloor.\]So, for example, let $k=l=8$, then

\[\left\lfloor\frac{n}{10^{8}}\right\rfloor = \left\lfloor\frac{y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor.\]Assuming that $n$ is of $10$ digits, the left-hand side is precisely the first $2$ digits of $n$, while the right-hand side is just the right-shift of $y$ by $D$-bits.

On the other hand, the next $2$ digits of $n$ can be computed as

\[\left(\left\lfloor\frac{n}{10^{6}}\right\rfloor \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right) = \left(\left\lfloor\frac{10^{2}y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right).\]Note that, if we write $y$ as $y=2^{D}q + r$ where $q$ is the quotient and $r$ is the remainder, then

\[10^{2}y = 2^{D}(10^{2}q) + 10^{2}r,\]so

\[\left(\left\lfloor\frac{10^{2}y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right) = \left(\left(10^{2}q + \left\lfloor\frac{10^{2}r}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor\right) \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right) = \left(\left\lfloor\frac{10^{2}r}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right).\]Also, since $r<2^{D}$, $\left\lfloor\frac{10^{2}r}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor$ is strictly less than $10^{2}$, so we get

\[\left(\left\lfloor\frac{n}{10^{6}}\right\rfloor \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right) = \left\lfloor\frac{10^{2}r}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor.\]This means that, in order to compute the next $2$ digits of $n$, we first obtain the remainder of $y$ divided by $2^{D}$, and then multiply $10^{2}$ to it, and then obtain the quotient of it divided by $2^{D}$. In other words, we just need to first obtain the lowest $D$-bits, multiply $10^{2}$ to it, and then right-shift the result by $D$-bits. As you can see, we only need $1$ multiplication here.

This trend continues: to compute the next $2$ digits of $n$, we only need to obtain the lowest $D$-bits, multiply $10^{2}$, and then right-shift the result by $D$-bits, so in particular we only need $1$ multiplication for generating each pair of $2$ digits. Indeed, it can be inductively shown that if we write $y_{0}=y$ and $y_{i+1} = 10^{2}(y_{i}\ \operatorname{mod}\ 2^{D})$, then

\[\left(\left\lfloor\frac{n}{10^{k-2i}}\right\rfloor \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right) = \left\lfloor\frac{y_{i}}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor\]holds for each $i=0,1,2,3,4$.

How to compute $y$?

Alright, so we get that having $y$ satisfying

\[n = \left\lfloor\frac{10^{k}y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor\]is pretty useful for our purpose. The next question is how to find such $y$. Note that the above equality is equivalent to the inequality

\[n \leq \frac{10^{k}y}{2^{D}} < n+1,\]or

\[\tag{$*$} \frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}} \leq y < \frac{2^{D}(n+1)}{10^{k}}.\]Assuming $2^{D}\geq 10^{k}$, $y=\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}}\right\rceil$ will obviously do the job, but computing $\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}}\right\rceil$ might be nontrivial. Hence, let us first try something easier:

\[y = n\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil.\]Here, $\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil$ is just a constant and is not dependent on $n$, so computing $y$ is just a single integer multiplication.

With $k=8$ and $n<2^{32}$, we can show that this $y$ always satisfies $(*)$ if we take $D\geq 57$; we just need to find the smallest $D$ satisfying $(2^{32}-1)\left(\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil - \frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}\right) < \frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}$. Hence, choosing $D=57$, we get the magic number

\[\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil = 1441151881.\]This leads us to the following code for always printing $10$ digits of given $n$ with possible leading zeros:

char* itoa_always_10_digits(std::uint32_t n, char* buffer) {

constexpr auto mask = (std::uint64_t(1) << 57) - 1;

auto y = n * std::uint64_t(1441151881);

std::memcpy(buffer + 0, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y &= mask;

y *= 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 2, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y &= mask;

y *= 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 4, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y &= mask;

y *= 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 6, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y &= mask;

y *= 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 8, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 10;

}

(Demo: https://godbolt.org/z/9c4Mb76hc)

The constant $1441151881$ is only of $31$-bits and multiplications are performed in $64$-bits so there is no overflow.

Consideration of variable length

One can easily modify the above algorithm to omit printing leading decimal zeros and align the output to the left-most position of the buffer. However, the resulting algorithm is not very nice; although it only performs no more than $5$ multiplications, it always performs $5$ multiplications, even for short numbers like $n=15$.

What James Anhalt did with this is complete separation of the code paths for all possible lengths of $n$. I mean, something like this:

// /\____________

// / \______ \______

// /\ \ \ \ \

// 0 1 /\ /\ /\ /\

// 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

char* itoa_var_length(std::uint32_t n, char* buffer) {

if (n < 100) {

if (n < 10) {

// 1 digit.

}

else {

// 2 digits.

}

}

else if (n < 100'0000) {

if (n < 1'0000) {

if (n < 1'000) {

// 3 digits.

}

else {

// 4 digits.

}

}

else {

if (n < 10'0000) {

// 5 digits.

}

else {

// 6 digits.

}

}

}

else if (n < 1'0000'0000) {

if (n < 1000'0000) {

// 7 digits.

}

else {

// 8 digits.

}

}

else if (n < 10'0000'0000) {

// 9 digits.

}

else {

// 10 digits.

}

}

It sounds pretty crazy, but it does the job quite well.

Now, recall that our main job is to find $y$ satisfying

\[n = \left\lfloor\frac{10^{k}y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor.\]Note that the choice $k=8$ was to make sure that $\left\lfloor\frac{y}{2^{D}}\right\rfloor$ is the first $2$ digits, given that $n$ is of $10$ digits. Since $n$ is not always of $10$ digits, we may take different $k$’s for each branch. For example, when $n$ is of $3$ digits, we may want to choose $k=2$. Then since $n\leq 999$ in this case, the choice

\[y = n\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil\]is valid for any $D\geq 12$, as $999\cdot \left(\left\lceil\frac{2^{12}}{10^{2}}\right\rceil - \frac{2^{12}}{10^{2}}\right) < \frac{2^{12}}{10^{2}}$ holds. In this case, it is in fact better to choose $D=32$ rather than $D=12$, because in platforms such as x86 obtaining the lower half of a $64$-bit integer is basically no-op.

As a result, the first digit of $n$ can be computed as

\[\left\lfloor\frac{n}{10^{2}}\right\rfloor = \left\lfloor\frac{y}{2^{32}}\right\rfloor = \left\lfloor\frac{\lceil 2^{32}/10^{2} \rceil n}{2^{32}}\right\rfloor = \left\lfloor\frac{42949673\cdot n}{2^{32}}\right\rfloor,\]and the remaining $2$ digits can be computed as

\[\left(\left\lfloor\frac{n}{10^{0}}\right\rfloor \ \operatorname{mod}\ 10^{2}\right)= \left\lfloor\frac{10^{2}(y\ \operatorname{mod}\ 2^{32})}{2^{32}}\right\rfloor.\]Similarly, we can choose $D=32$ (with the above $y$ with different $k$’s) for $n$’s up to $6$ digits (so $k=0,2,4$), but for larger $n$ our simplistic analysis does not allow us to do so. For $n$’s with $7$ or $8$ digits, we set $k=6$, and it can be shown that $D=47$ does the job. For $n$’s with $9$ or $10$ digits, we set $k=8$, and as we have already seen $D=57$ does the job. With these choices of parameters, we get the following code:

// /\____________

// / \______ \______

// /\ \ \ \ \

// 0 1 /\ /\ /\ /\

// 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

char* itoa_var_length(std::uint32_t n, char* buffer) {

if (n < 100) {

if (n < 10) {

// 1 digit.

buffer[0] = char('0' + n);

return buffer + 1;

}

else {

// 2 digits.

std::memcpy(buffer, radix_100_table + n * 2, 2);

return buffer + 2;

}

}

else if (n < 100'0000) {

if (n < 1'0000) {

// 3 or 4 digits.

// 42949673 = ceil(2^32 / 10^2)

auto y = n * std::uint64_t(42949673);

if (n < 1'000) {

// 3 digits.

buffer[0] = char('0' + int(y >> 32));

y = std::uint32_t(y) * std::uint64_t(100);

std::memcpy(buffer + 1, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 3;

}

else {

// 4 digits.

std::memcpy(buffer + 0, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

y = std::uint32_t(y) * std::uint64_t(100);

std::memcpy(buffer + 2, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 4;

}

}

else {

// 5 or 6 digits.

// 429497 = ceil(2^32 / 10^4)

auto y = n * std::uint64_t(429497);

if (n < 10'0000) {

// 5 digits.

buffer[0] = char('0' + int(y >> 32));

y = std::uint32_t(y) * std::uint64_t(100);

std::memcpy(buffer + 1, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

y = std::uint32_t(y) * std::uint64_t(100);

std::memcpy(buffer + 3, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 5;

}

else {

// 6 digits.

std::memcpy(buffer + 0, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

y = std::uint32_t(y) * std::uint64_t(100);

std::memcpy(buffer + 2, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

y = std::uint32_t(y) * std::uint64_t(100);

std::memcpy(buffer + 4, radix_100_table + int(y >> 32) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 6;

}

}

}

else if (n < 1'0000'0000) {

// 7 or 8 digits.

// 140737489 = ceil(2^47 / 10^6)

auto y = n * std::uint64_t(140737489);

constexpr auto mask = (std::uint64_t(1) << 47) - 1;

if (n < 1000'0000) {

// 7 digits.

buffer[0] = char('0' + int(y >> 47));

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 1, radix_100_table + int(y >> 47) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 3, radix_100_table + int(y >> 47) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 5, radix_100_table + int(y >> 47) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 7;

}

else {

// 8 digits.

std::memcpy(buffer + 0, radix_100_table + int(y >> 47) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 2, radix_100_table + int(y >> 47) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 4, radix_100_table + int(y >> 47) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 6, radix_100_table + int(y >> 47) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 8;

}

}

else {

// 9 or 10 digits.

// 1441151881 = ceil(2^57 / 10^8)

constexpr auto mask = (std::uint64_t(1) << 57) - 1;

auto y = n * std::uint64_t(1441151881);

if (n < 10'0000'0000) {

// 9 digits.

buffer[0] = char('0' + int(y >> 57));

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 1, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 3, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 5, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 7, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 9;

}

else {

// 10 digits.

std::memcpy(buffer + 0, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 2, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 4, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 6, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

y = (y & mask) * 100;

std::memcpy(buffer + 8, radix_100_table + int(y >> 57) * 2, 2);

return buffer + 10;

}

}

}

(Demo: https://godbolt.org/z/froGhEn3s)

Note: The paths for $(2k-1)$-digits case and $2k$-digits case share a lot of code, so one might try to merge the code for printing $(2k-2)$ remaining digits while leaving in separate branches only the code for printing the leading $1$ or $2$ digits. However, it seems that such a refactoring causes the code to perform worse, probably because the number of additions performed is increased. Nevertheless, that is also one viable option, especially regarding the code size.

Better choices for $y$

The above code is pretty good for $n$’s up to $6$ digits, but not so much for longer $n$’s, as we have to perform masking in addition to multiplication and shift for each $2$ digits. This is due to $D$ being not equal to $32$, so it will be beneficial if we can choose $D=32$ even for $n$’s with digits more than $6$. And it turns out that we can.

The reason we had to choose $D>32$ was due to our poor choice of $y$:

\[y = n\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil.\]Recall that we do not need to choose $y$ like this; all we need to ensure is that $y$ satisfies the inequality

\[\tag{$*$} \frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}} \leq y < \frac{2^{D}(n+1)}{10^{k}}.\]Slightly generalizing what we have done, let us suppose that we want to obtain $y$ by computing

\[y = \left\lfloor\frac{nm}{2^{L}}\right\rfloor\]for some positive integer constants $m$ and $L$. Then the inequality $(*)$ can be rewritten as

\[\tag{$**$} \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}}\right\rceil \leq \frac{m}{2^{L}} < \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}(n+1)}{10^{k}}\right\rceil.\]At the time of writing this post, I am not quite sure if there is an elegant way to obtain the precise admissible range of $m$ and $L$ for the above inequality with any given range of $n$, but a reasonable guess is that

\[m = \left\lceil\frac{2^{D+L}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil + 1\]will often do the job. Indeed, in this case we have

\[\frac{mn}{2^{L}} \geq \frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}} + \frac{n}{2^{L}},\]so the left-hand side of \((**)\) is always satisfied if

\[2^{L} \leq n\]holds for all $n$ in the range. On the other hand, we have

\[\frac{mn}{2^{L}} < \frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}} + \frac{n}{2^{L-1}},\]so the right-hand side of \((**)\) is always satisfied if

\[\frac{n}{2^{L-1}}\leq \frac{2^{D}}{10^{k}},\]or equivalently,

\[\frac{10^{k}n}{2^{D-1}} \leq 2^{L}\]holds for all $n$ in the range.

Thus for example, when $n$ is of $7$ or $8$ digits (so $n\in[10^{6}, 10^{8}-1]$), $k=6$, and $D=32$, it is enough to have

\[\frac{10^{6}(10^{8} - 1)}{2^{31}} \leq 2^{L} \leq 10^{6},\]which is equivalent to

\[16 \leq L \leq 19.\]Hence, we take $L = 16$ and accordingly $m = 281474978$. Of course, since $m$ is even we can equivalently take $L = 15$ and $m = 140737489$ as well, so this method of analysis is clearly far from being tight.

(In fact, it can be exhaustively verified that the left-hand side of $(*)$ is maximized when $n=1000795$, while the right-hand side is minimized when $n=10^{8}-1$, which together yield the inequality

\[\frac{4298381796}{1000795} \leq \frac{m}{2^{L}} < \frac{429496729600}{99999999}.\]The minimum $L$ allowing an integer solution for $m$ to the above inequality is $L=15$ and in this case $m = 140737489$ is the unique solution.)

When $n$ is of $9$ or $10$ digits, a similar analysis does not give the best result, especially for $10$ digits it fails to give any admissible choice of $L$ and $m$. Nevertheless, it can be exhaustively verified that, when $k=8$ and $D=32$, if we set $L = 25$ and

\[m = \left\lceil\frac{2^{D+L}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil + 1 = 1441151882,\]then

\[n = \left\lfloor \frac{10^{k}\lfloor nm/2^{L} \rfloor}{2^{D}} \right\rfloor\]holds for all $n\in [10^{8}, 10^{9}-1]$, and similarly, if we set $L = 25$ and

\[m = \left\lceil\frac{2^{D+L}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil = 1441151881,\]then

\[n = \left\lfloor \frac{10^{k}\lfloor nm/2^{L} \rfloor}{2^{D}} \right\rfloor\]holds for all $n\in [10^{9}, 2^{32}-1]$, so we can still take

\[y = \left\lfloor \frac{nm}{2^{L}} \right\rfloor\]with the above $L$ and $m$.

(In fact, applying what we have done for $7$ or $8$ digits into the case of $9$ digits gives $L=26$ and $m=2882303763$. However, $1441151882$ is a better magic number than $2882303763$, because the former is of $31$-bits while the latter is of $32$-bits. This trivially-looking difference actually quite matters on platforms like x86, because when computing $y=\left\lfloor\frac{nm}{2^{L}}\right\rfloor$, we want to leverage the fast imul instruction, but imul sign-extends the input immediate constant when performing $64$-bit multiplication. Hence, if the magic number is of $32$-bits, the multiplication cannot be done in a single instruction, and the magic number must be first loaded into a register and then zero-extended.)

Therefore, we are indeed able to always choose $D=32$, which results in the following code:

char* itoa_better_y(std::uint32_t n, char* buffer) {

std::uint64_t prod;

auto get_next_two_digits = [&]() {

prod = std::uint32_t(prod) * std::uint64_t(100);

return int(prod >> 32);

};

auto print_1 = [&](int digit) {

buffer[0] = char(digit + '0');

buffer += 1;

};

auto print_2 = [&] (int two_digits) {

std::memcpy(buffer, radix_100_table + two_digits * 2, 2);

buffer += 2;

};

auto print = [&](std::uint64_t magic_number, int extra_shift, auto remaining_count) {

prod = n * magic_number;

prod >>= extra_shift;

auto two_digits = int(prod >> 32);

if (two_digits < 10) {

print_1(two_digits);

for (int i = 0; i < remaining_count; ++i) {

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

}

}

else {

print_2(two_digits);

for (int i = 0; i < remaining_count; ++i) {

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

}

}

};

if (n < 100) {

if (n < 10) {

// 1 digit.

print_1(n);

}

else {

// 2 digit.

print_2(n);

}

}

else {

if (n < 100'0000) {

if (n < 1'0000) {

// 3 or 4 digits.

// 42949673 = ceil(2^32 / 10^2)

print(42949673, 0, std::integral_constant<int, 1>{});

}

else {

// 5 or 6 digits.

// 429497 = ceil(2^32 / 10^4)

print(429497, 0, std::integral_constant<int, 2>{});

}

}

else {

if (n < 1'0000'0000) {

// 7 or 8 digits.

// 281474978 = ceil(2^48 / 10^6) + 1

print(281474978, 16, std::integral_constant<int, 3>{});

}

else {

if (n < 10'0000'0000) {

// 9 digits.

// 1441151882 = ceil(2^57 / 10^8) + 1

prod = n * std::uint64_t(1441151882);

prod >>= 25;

print_1(int(prod >> 32));

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

}

else {

// 10 digits.

// 1441151881 = ceil(2^57 / 10^8)

prod = n * std::uint64_t(1441151881);

prod >>= 25;

print_2(int(prod >> 32));

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

print_2(get_next_two_digits());

}

}

}

}

return buffer;

}

(Demo: https://godbolt.org/z/7TaqYa9h1)

Note: Looking at a port of James Anhalt’s original algorithm, it seems that the above code is probably a little bit better than the original implementation (which can be confirmed in the benchmark below) because the original algorithm performs an addition after the first multiplication and shift, for digit length longer than some value. With our choice of magic numbers, that is not necessary.

Benchmark

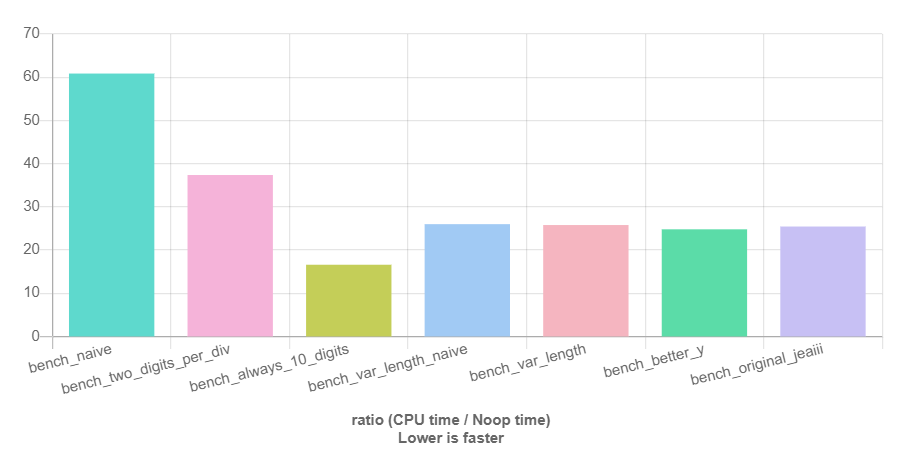

Alright, now let’s compare the performance of these implementations.

Link: https://quick-bench.com/q/ieIpsBhWC751YUhyVS2OE83dTO4

itoa_var_length_naive is a straightforward variation of itoa_var_length doing the naive quotient/remainder computation instead of playing with $y$. Well, compared to itoa_var_length_naive, the performance benefit of itoa_better_y seems not very impressive to be honest. Nevertheless, I still think the idea behind the algorithm is pretty intriguing.

Back to fixed-length case

So far we only have looked at the case of $32$-bit unsigned integers. For $64$-bit integers, what people typically do is to first divide the input number into several segments of $32$-bit integers, and then print them using methods for $32$-bit integers. In this case, typically only the first segment is of variable length and remaining segments are of fixed length. As we can see in the benchmark above, when the length is known we can do a lot better. For simplicity of the following discussion, let us suppose that the input integer is at most of $9$ digits and we want to always print $9$ digits with possible leading zeros.

While what we have done in itoa_always_10_digits is not so bad, we can certainly do better by choosing $D=32$ which eliminates the need for performing masking at each generation of $2$ digits. Recall that all we need to do is to find an integer $y$ satisfying

for given $n$. Since we want to always print $9$ digits, we take $k=8$. What’s different from the previous case is that now $n$ can be any integer in the range $[1,10^{9}-1]$ (ignoring $n=0$ case, but that is not a big deal), in particular it can be very small. In this case, one can show by exhaustively checking all possible $n$’s that the inequality

\[\tag{$**$} \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}}\right\rceil \leq \frac{m}{2^{L}} < \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}(n+1)}{10^{k}}\right\rceil\]does not have a solution, because the maximum value of the left-hand side is bigger than the minimum value of the right-hand side. Therefore, it is not possible to compute $y$ by just performing a multiplication followed by a shift.

Instead, we choose

\[y = \left\lfloor \frac{nm}{2^{L}} \right\rfloor + 1,\]which means that we indeed omit masking at each generation of $2$ digits, but at the cost of additionally performing an increment for the initial step of computing $y$.

With this choice of $y$, $(*)$ becomes

\[\tag{$**'$} \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}}\right\rceil - \frac{1}{n} \leq \frac{m}{2^{L}} < \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{2^{D}(n+1)}{10^{k}}\right\rceil - \frac{1}{n}\]instead of $(**)$. Then we can perform a similar analysis to conclude that $L = 25$ with

\[m = \left\lceil \frac{2^{D+L}}{10^{k}} \right\rceil = 1441151881\]do the job. In fact, an exhaustive check shows that we can even take $L = 24$ and $m = 720575941$.

EDIT: Recall that in the above, the range of $n$ is constrained into $[0,10^{9}-1]$. It turns out $L = 24$ with $m = 720575941$ works only up to $n = 1133989877$, and it starts to produce errors if $n \geq 1133989878$.

I derived a better, but still incomplete analysis here. After a while, I eventually obtained a complete algorithm for computing the optimal bounds, and wrote a program that does the analysis. The algorithm itself is not published anywhere at this moment.

Concluding remarks

I applied a minor variation of the algorithm explained here into my Dragonbox implementation to speed up digit generation, and the result was quite satisfactory. I think probably the complete branching for all possible lengths of the input is not a brilliant idea for generic applications, but the idea of coming up with $y$ that enables generating each pair of $2$ digits by only performing a multiply-and-shift is very clever and useful. I expect that this same trick might be applicable to other problems as well, fixed-precision floating-point formatting for example.

Leave a Comment