Fixed-precision formatting of floating-point numbers

Published:

TL;DR

This post is about an algorithm I developed for formatting IEEE-754 binary floating-point numbers in the fixed-precision form, like

printf.The algorithm is an alternative to Ryū-printf (not to be confused with Ryū), and is based on a similar trick that allows the computation to be done completely inside a bounded-precision integer arithmetic of fairly small maximum precision.

But it is not just a variant of Ryū-printf, because the core formula that powers it is quite different from the corresponding one of Ryū-printf.

The precomputed cache table it needs is much smaller than that of Ryū-printf; more importantly, there is a fairly flexible and systematic way of choosing the amount of trade-off between the performance and the table size.

And still, the performance is comparable to Ryū-printf.

The algorithm really in a nutshell:

Precompute and store sufficiently many bits of sufficiently many powers of $5$.

Profit.

If you are a “shut up and show me the code” type of person, please go down here, then you will find a benchmark graph and the link to the source code.

I would not consider this work to be “Done” yet, as there are lots of things that could be improved further. Especially the implementation right now is far from complete, is a complete mess, the exact anti-thesis of the DRY principle, and furthermore I haven’t done a good enough amount of formal testing.

Introduction

When formatting binary floating-point numbers into decimal strings, there are two common approaches: the shortest form with the roundtrip guarantee, and the fixed-precision form. The main topic of this post is the latter, but let me first briefly explain the former in order to emphasize how it differs from the latter.

As the name “shortest form” suggests, the methods falling into the this category find the shortest decimal representation of the input binary floating-point number that will still be interpreted as the input number by any correct parser. In order to understand what this means, we first have to know what do we mean by “a correct parser”. Note that with a limited amount of bits, we can never encode all real numbers into a floating-point data without loss. Thus, whenever we want to convert a real number into a floating-point data type, we should round the given number to one of the numbers that can be exactly represented in the chosen data type. A correct parser thus means an algorithm which consistently performs this conversion according to given rounding rules, without error. In practice, for a given instance $w$ of a floating-point data type, thus there is an interval of real numbers that, when given to a correct parser, are converted to $w$. The job of the shortest form formatting methods aforementioned is then to look into that interval and figure out the number with the shortest decimal description.

In contrast, the methods in the second category do not perform such a fancy search. What they do is just literally evaluate the exact value of the given binary floating-point number into decimal, and then cut the digits after the prescribed precision with rounding.

For example, the exact value of the binary floating-point number 0x1.3e9e4e4c2f344p+199 (written in hexfloats) is $999999999999999949387135297074018866963645011013410073083904$. Interpreting it as an instance of IEEE-754 binary64 format (which is what the data type double usually means) with the default rounding rules, the methods from the first category will output something like $1\times 10^{60}$. However, if configured to print only $17$ decimal digits, methods from the second category will output $9.9999999999999995 \times 10^{59}$, under the default rounding rules.

Note that, here by shortest we do not mean the smallest number of characters in the final string; rather, this means the smallest number of decimal significand digits. The reason for mentioning this difference is because there is another, completely orthogonal classification of floating-point formatting methods: formatting into the fixed-point form, the scientific (aka the floating-point) form, or the general form. The fixed-point form means the usual $123.456$ or alike, while the scientific form means something like $1.234 \times 10^{17}$. In the former, we always put the decimal point “$.$” at its absolute position (between the $1$’s digit and the $0.1$’s digit), while in the latter, we always put the decimal point right after the first non-zero digit, and then append something like “$\times 10^{17}$” to indicate the distance of that position of the decimal point from its correct absolute position. The general form, on the other hand, chooses the better one between the fixed-point form and the scientific form according to certain criteria, which are usually some incarnation of the idea: “prefer the fixed-point form until it becomes too long”.

Note that the exact number of characters is highly dependent on many details of formatting, especially whether it is in the fixed-point form or the scientific form. However, that distinction has nothing to do with what specific digits will be in the final string. The one that determines the actual numbers that will appear in the final string is the choice between the shortest roundtrip versus the fixed-precision. For this reason, details like the exact number of characters in the final string are less interesting, while the aforementioned choice between two categories is something more fundamental.

Note.

The distinction between the terms “fixed-precision” and “fixed-point” is not quite standard. Indeed, in their literal sense, they just sound like the same thing, which is probably the reason for the confusion around them. Therefore, it is worth re-emphasizing that these two mean completely different and orthogonal things in this post. I hope there are some standard terms that can distinguish them unambiguously, but I have not found any existing ones, so I am currently just using “fixed-precision” vs “fixed-point”. Please let me know if there are standard terms or if you have a better suggestion.

Historically, fixed-precision methods came first. For example, functions like printf and its friends in C’s standard library only offer fixed-precision formatting. However, arguably the shortest roundtrip is a more natural approach, and it is becoming more common recently. I really think there are not so many situations where fixed-precision is absolutely desired, especially with absurdly large precision. Like, it simply makes no sense to print $100$ decimal digits of an instance of double, because it far exceeds the natural precision of the data type and it never contributes to better precision. In fact, I would even say that such an excessive number of digits promotes a false sense of precision, so should be avoided in general. If someone is purely curious about the exact decimal digits of the exact number stored in the memory, then well, that could be a valid reason for doing something like printf("%.100e", x), but I cannot think of any other reason.

A typical scenario when fixed-precision formatting is desired, rather than the shortest roundtrip, is when your output window is too small for typical outputs from the latter, or when you need the aesthetic appeal of nice alignment. Indeed, fixed-precision formatting is the natural choice for such a case. One might insist on using the shortest roundtrip formatting for such a case and then cut the results at a certain precision, but that would be considered double-rounding, which should be actively avoided. This is a very common and valid usage of fixed-precision formatting, but note that we never need things like printf("%.100e", x) in this case.

A funny thing about fixed-precision formatting is that it is a hard problem, in my opinion a way harder problem than shortest roundtrip formatting, contrary to its simpler look. And the reason is precisely because the precision requested by the user can be arbitrarily large. This lengthy blog post would not have been needed at all if we could only care about the small digits case. But if dealing with the large digits case requires too much effort while it is not something anyone really needs, then should we really need to care about it?

The thing is, someone still needs to implement it even though nobody really needs it in practice because, in my limited understanding, it is required by someone else for whatever reason, regardless of whether it is due to a sane engineering rationale or not. Seriously! Like, the C/C++ standards say it’s allowed to do printf("%.100e", x), so C/C++ standard library implementers have no choice but to make it work correctly. (To be honest, I am not a language lawyer and not 100% sure if this claim is completely correct. Apparently, it seems the only restrictions on the precision field in the format string are that (1) negative numbers are ignored, and (2) the number should be representable as an int, which allows even crazier things like printf("%.2000000000e", x). However, I am not completely sure if implementations are required to output the perfectly right answer all the time, or it is okay to just do their best.)

Actually, there is another quite compelling reason why it would be valuable for someone to think about this problem: a fast fixed-precision formatting algorithm can be used as a subroutine of a correct parser. For example, let us say that we want to convert the decimal number $1.70141193601674033557522515689509748736000000……000001 \times 10^{38}$ into IEEE-754 binary32 encoded binary number (which is what the data type float usually means). In this case, we cannot decide whether the number is closer to 0x1.p+127 or to 0x1.000002p+127 until we fully read the input. Note that doing this conversion with the straightforward multiplication of the power of $10$ with the significand requires handling of numbers with arbitrarily large precision. Or, an alternative strategy would be to generate the decimal digits of the midpoint between 0x1.p+127 and 0x1.000002p+127 using a fixed-precision formatting algorithm, and compare those digits with the input digits. This turns out to be a quite successful strategy, as demonstrated here.

Actually, there is yet another reason for me to think about this problem: it is interesting enough to catch my attention😃 This post is about my attempt at solving this problem so far.

I want to mention before getting into the main point that this work is a continuation from my previous work on Dragonbox, which is an algorithm for spitting out the shortest roundtrip output. As I pointed out, the possibility of excessive precision, which is a quite niche edge case as I claimed above, makes this work much more difficult than Dragonbox. As is often the case in many engineering problems, it is the niche edge case that makes the thing 100x more complicated :)

So what is the goal precisely?

Let’s summarize what exactly the problem we want to solve is:

For a given binary floating-point number $w$ and a positive integer $d$, how to print $d$ many decimal digits of $w$ with rounding, counting from the first nonzero digit?

First, I want to mention that I have stated the number of digits is counted from the first nonzero digit. Sometimes the users may have a different idea about the number of digits; for example it might be the number of digits after the decimal point. For instance, if our number is $0.00175$, then it has $3$ decimal digits counting from the first nonzero digit (which is $1$), but it has $5$ decimal digits after the decimal point. However, this difference will not significantly affect the core of the algorithm, so I will stick to what I have stated.

Note that, of course, this is not a very interesting problem if all we want to do is just printing the digits. However, typically this is done with so-called “big integer” arithmetic. Big integer arithmetic is notoriously slow, and also typically involves heap allocation, which is an absolute no-no in certain domains. In our case, it is probably easier to at least avoid heap allocations since the numbers we need to deal with are not horrendously large. But even without heaps, big integer arithmetic is still very heavy; the typical performance of division is especially quite dreadful. With this in mind, here is a revised version of our goal:

For a given binary floating-point number $w$ and a positive integer $d$, how to quickly print $d$ many decimal digits of $w$ with rounding, counting from the first nonzero digit, with reasonably-sized big integer arithmetic only, possibly avoiding divisions?

The current state-of-the-art algorithm to my knowledge, Ryū-printf, developed by Ulf Adams in 2019, already achieves this goal. Assuming IEEE-754 binary64, the maximum size of integers appearing inside the algorithm is $256$-bits, which is quite reasonable. It also does not directly do long division. As a consequence, Ryū-printf is very fast, and especially for large precision, it is much faster than other algorithms that use regular big integers.

However, the biggest problem with Ryū-printf is that it relies on a gigantic precomputed data table, which is about $\mathbf{102}$ KB. Compare this to the size of the Dragonbox table, which is only of $9.7$ KB. Moreover, it is not so difficult to trade a little bit of performance to compress this $9.7$ KB table down to $584$ bytes. However, it is not obvious if can we do something similar for Ryū-printf.

Back in 2020, I tried to implement Ryū-printf and was able to come up with an implementation strategy that allows us to compress the table down into $39$ KB, while delivering performance that is more or less equivalent to the reference implementation. But you know, $39$ KB is still huge. More importantly, I was not aware of any way to reasonably trade more performance for a smaller table size. I mean, I knew of a way to make the table smaller by sacrificing some performance (and I’m pretty sure Ulf Adams is probably also aware of a similar idea), but I couldn’t make it smaller than, say, $10$ KB.

The large table size is essentially due to the possibility of excessive precision, which, as I pointed out several times, is not the common use case. I do not think it’s a good idea to have a table as large as $39$ KB just to be prepared for a very rare possibility. If we can reduce the size of the table while delivering a reasonable performance for the common case, i.e., the small precision case, then that would be nice.

So here is the second revision of our goal:

For a given binary floating-point number $w$ and a positive integer $d$, how to quickly print $d$ many decimal digits of $w$ with rounding, counting from the first nonzero digit, with reasonably-sized big integer arithmetic only, possibly avoiding divisions, and also with reasonably-sized precomputed cache data, preferably with a generic method of trading the performance with the data size? Also the performance when $d$ is small is more important than the performance when $d$ is large.

As a spoiler, this is what I concluded. Assuming IEEE-754 binary64, the exact same table from Dragonbox (of size $9.7$ KB, or $584$ bytes with a little bit of performance cost) is mostly enough when $d$ is small, and the heaviest arithmetic operation we need is $128$-bit $\times$ $64$-bit multiplication. For any other cases not covered by this table, we only need an additional table of size $\mathbf{3.6}$ KB, and the heaviest arithmetic operation we need is $192$-bit $\times$ $64$-bit multiplication.

Furthermore, it is possible to flexibly trade a larger maximum size of operand to multiplications for a smaller size of this additional table, without compromising the performance of the cases covered by the Dragonbox table. For instance, it is possible to reduce the size of the additional table to $\mathbf{580}$ bytes at the cost of requiring $960$-bit $\times$ $64$-bit multiplications instead of $192$-bit $\times$ $64$-bit multiplications.

Acknowledgement

Ryū-printf is the first source of inspiration, although what I ended up with is not directly based on it. Many other crucial inspirations came from private conversations with James Edward Anhalt III about his integer formatting algorithm and related topics. This paper by Lemire et al on remainder computation was also influential. The work by Raffaello Giulietti and Dmitry Nadezhin, on which my previous work on shortest roundtrip formatting is directly based, is where I learned about the relevancy of the concept of continued fractions, which is undoubtedly the most crucial element in the development of this algorithm. Thanks to Shengdun Wang for many discussions on possible optimizations. He is also the one who told me that fixed-precision formatting could be used as a subroutine for correct parsing back in 2019-2020. Special thanks to Seung uk Jang for reviewing this lengthy post.

The core idea

Now let’s get into the main idea of the algorithm I came up with. Following the notation I used in my paper on Dragonbox, we write our binary floating-point number as

\[w = \pm f_{c}\cdot 2^{e},\]where $f_{c}$ is an unsigned integer and $e$ is an integer within certain range. For IEEE-754 binary32, $f_{c}$ is at most $2^{24}-1$ and $e$ is from $-149$ to $104$. More precisely, $f_{c}$ is also at least $2^{23}$ unless $e=-149$ (see this). Also, for IEEE-754 binary64, $f_{c}$ is at most $2^{53}-1$ and $e$ is from $-1074$ to $971$, and $f_{c}$ is also at least $2^{52}$ unless $e=-1074$. For simplicity, we will only focus on IEEE-754 binary64 in this post, but there is nothing deep about this assumption and most of the discussions can be extended to other common formats without fundamental difficulties.

Since we are also interested in printing out the digits of midpoints (for the application into parsing), we will in fact work with the form

\[w = \pm 2f_{c}\cdot 2^{e-1}\]so that we can easily replace $w$ by the midpoint

\[m_{w}^{+} = \pm (2f_{c} + 1) \cdot 2^{e-1}\]if we want. For convenience, we will just use the notation $w$ to mean either of the above two, and use the notation $n$ to denote the significand part of it, i.e., either $2f_{c}$ or $2f_{c}+1$.

Also, we will always assume that $w$ is strictly positive since once positive case is done then the other cases, zero, negative, infinities, or NaN’s, can be done easily.

So what does it mean by obtaining decimal digits from $w$? By the $k$th decimal digit of $w$, we mean the number

\[\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k} \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 10\right) = \left(\left\lfloor n \cdot (2^{e+k-1}\cdot 5^{k}) \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 10\right).\]In fact, we do not need to take $\mathrm{mod}\ 10$. Rather, it is advantageous to consider a higher power of $10$ instead of $10$ for various reasons. Hence, we may consider

\[\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k} \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{\eta}\right) = \left(\left\lfloor n \cdot (2^{e+k-1}\cdot 5^{k}) \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{\eta}\right)\]for some positive integer $\eta$. Note that once we get the above which is an integer of (at most) $\eta$-many decimal digits, we can leverage fast integer formatting algorithms (like the one by James Edward Anhalt III) to extract decimal digits out of it. Considering $\eta>1$ essentially means that we work with a block of multiple decimal digits at once, rather than with individual digits. I will call this block of digits a segment. Of course, to really leverage fast integer formatting algorithms, we may need to choose $\eta$ to be not very big. Maybe the largest value for $\eta$ we can think of is $9$ because $10^{9}$ is the highest power of $10$ that fits in $32$-bits, or maybe $19$ if we consider $64$-bits instead. However, it turns out, we can in fact take $\eta$ even larger than that, which is a crucial factor for the space-time trade off we are aiming for. We will discuss this later.

Abstractly speaking, what we want to do is to compute

\[\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ D\]where $n=1,\ \cdots\ ,n_{\max}$ is a positive integer, $x$ is a positive rational number, and $D$ is a positive integer. What this expression means is this: we multiply $n$ to the numerator of $x$, divide it by the denominator of $x$, take the quotient, then divide the quotient by $D$ and take the remainder.

As I mentioned in the previous section, we want to avoid big integer arithmetic of arbitrary precision (especially division) so we do not want to do this computation as literally described above. The required precision for doing so is indeed quite big. For instance, let’s say $D=10^{9}$, $e=-1074$ and $k=560$ so that we are obtaining the 552nd~560th digits of $w$ after the decimal point. Then the numerator of $x$ is $5^{560}$ which is $1301$-bit long, so we have to compute this $1301$-bit long number, multiply our $n$ into this $1301$-bit long number, and then divide it by $2^{515}$ (which is the denominator of $x$ in this case) which means throwing the last $515$-bits away, and then compute the division by $D$ for the resulting $800$-ish-bits number. Or, let $e=971$ and $k=-100$ so that we are obtaining 9 digits up to the 101st digit before the decimal point. Then the numerator of $x$ is $2^{870}$ and the denominator is $5^{100}$, so we may need to first left-shift $n$ by $870$-bits, and then divide it by either $5^{100}$ after computing $5^{100}$ or by lower powers of $5$ iteratively. Either way, we end up with dividing a number that is $900$-ish-bits long.

(In fact, by performing big integer multiplications in decimal, that is, using this or a slight extension of it, we can avoid doing divisions by big integers. The idea, which I learned from Shengdun Wang, is that we can always turn the denominator of $x$ into a power of $10$ by adjusting the numerator accordingly, and in decimal, dividing by a power of $10$ is just a matter of cutting off some digits. The cost to pay is that multiplication of integers in decimal involves a lot of divisions by constant powers of $10$ (but fortunately of small dividends). Some cool things about this trick are that it generalizes trivially to any binary floating-point formats, and also that we can store precomputed powers of $5$ and $2$ if needed, while the total size of the table can be quite easily tuned according to any given requirements. This is all good, but I think the method that will be explained below is probably way faster.)

The following theorem from the paper on Dragonbox again proves itself to be very useful for computing $\left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$:

Theorem 4.2.

Let $x$ be a positive real number and $n_{\max}$ a positive integer. Then for a positive real number $\xi$, we have the followings.

If $x=\frac{p}{q}$ is a rational number with $q\leq n_{\max}$, then we have \(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor = \left\lfloor n\xi \right\rfloor\) for all $n=1,\ \cdots\ ,n_{\max}$ if and only if \(x \leq \xi < x + \frac{1}{vq}\) holds, where $v$ is the greatest integer such that $vp\equiv -1\ (\mathrm{mod}\ q)$ and $v\leq n_{\max}$.

If $x$ is either irrational or a rational number with the denominator strictly greater than $n_{\max}$, then we have \(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor = \left\lfloor n\xi \right\rfloor\) for all $n=1,\ \cdots\ ,n_{\max}$ if and only if \(\frac{p_{*}}{q_{*}} \leq \xi < \frac{p^{*}}{q^{*}}\) holds, where \(\frac{p_{*}}{q_{*}}\), \(\frac{p^{*}}{q^{*}}\) are the best rational approximations of $x$ from below and above, respectively, with the largest denominators \(q_{*},q^{*}\leq n_{\max}\).

The core idea is to take $\xi=\frac{mD}{2^{Q}}$ for certain positive integers $m$ and $Q$ depending on $x$ and $n_{\max}$ (but not on $n$). Suppose $\xi=\frac{mD}{2^{Q}}$ satisfies the conditions given above, then, the following magic happens:

\[\begin{aligned} \left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right) &= \left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor}{D} \right\rfloor D \\ &= \left\lfloor n\xi \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{\left\lfloor n\xi \right\rfloor}{D} \right\rfloor D \\ &= \left\lfloor n\xi \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{n\xi}{D} \right\rfloor D \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{nmD}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor \frac{nm}{2^{Q}}\right\rfloor D \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{nmD - \lfloor nm/2^{Q} \rfloor D2^{Q}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{(nm - \lfloor nm/2^{Q} \rfloor 2^{Q})D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor. \end{aligned}\]In other words, we first multiply $m$ to $n$, take the lowest $Q$-bits out of it, multiply $D$ to the resulting $Q$-bits, and then throw away the lowest $Q$-bits. Then what’s remaining is precisely equal to $\left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$.

This trick is in fact no different from the idea presented in this paper by Lemire et al. But here we are relying on a more general result (Theorem 4.2) which gives a much better bound when the denominator of $x$ is large. A similar, slightly different idea is also used in the integer formatting algorithm I analyzed in the previous post. Really, I consider the algorithm presented here as a simple generalization of those works.

In addition to turning a modular operation into a multiplication followed by some bit manipulations, we get an even nicer achievement: we only need to know the lowest $Q$-bits of $m$, rather than all bits of $m$, because we are going to take $\mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}$ right after multiplying $n$ to it. That is, $\left(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right)$ is equal to $\left(n\left(m\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right)\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right)$.

By Theorem 4.2, given $x$ and $n_{\max}$, any $m$ and $Q$ such that $\xi = \frac{mD}{2^{Q}}$ satisfies the conditions will allow us to compute $\left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$ using the formula

\[\label{eq:core formula} \left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right) = \left\lfloor \frac{\left(n\left(m\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right)\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right)D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor.\]Obviously, we want to choose $Q$ to be as small as possible because that will reduce the number of bits we need to throw into the computation, which both saves the memory and improves the performance. However, due to a reason that will become clear later in this section, it is beneficial to have a generic formula of $m$ that works for any large enough $Q$, rather than the one that allows us to choose the smallest $Q$. That generic formula we will use is:

\[m = \left\lceil \frac{2^{Q}x}{D} \right\rceil.\]This choice of $m$ kinda makes sense, because morally $\xi=\frac{mD}{2^{Q}}$ is meant to be a good approximation of $x$, so $m$ should be a good approximation of $\frac{2^{Q}x}{D}$, but $m$ needs to be at least $\frac{2^{Q}x}{D}$ when the denominator of $x$ is small, due to the first case of Theorem 4.2, so we choose the ceiling.

With this $m$, $\xi = \frac{mD}{2^{Q}}$ is automatically at least $x$, so the left-hand sides of the inequalities given in Theorem 4.2 are always satisfied, thus we only need to care about the right-hand sides. That is, we look for $Q$ such that

\[\label{eq:core inequality} \xi = \frac{\left\lceil 2^{Q}x/D\right\rceil D}{2^{Q}} < \begin{cases} x + \frac{1}{vq} & \textrm{if $x=\frac{p}{q}$ is rational with $q\leq n_{\max}$},\\ \frac{p^{*}}{q^{*}} & \textrm{otherwise} \end{cases}\]holds. Thanks to the wonderful theory of continued fractions, we can efficiently compute the right-hand side of the above inequality for any given $x$ and $n_{\max}$, allowing us to find the smallest $Q$ that satisfies the inequality.

This leads us to the following strategy for computing $\left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$:

For all values of $x$ that we care about, find the smallest $Q$ satisfying the inequality $\eqref{eq:core inequality}$, and store the lowest $Q$-bits of $m = \left\lceil\frac{2^{Q}x}{D}\right\rceil$ and $Q$ in a cache table. This is done only once, before runtime.

During runtime, for a given value of $x$, load the corresponding $(m\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})$ and $Q$ from the cache table. Then using the formula $\eqref{eq:core formula}$, which only requires some multiplications and bit manipulations, we can compute $\left(\left\lfloor nx\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$ for any given $n$.

In practice, however, this strategy is not directly applicable to our situation, because too much information needs to be stored. To illustrate this, recall that in our situation we have $x = 2^{e+k-1}\cdot 5^{k}$, so a different pair $(e,k)$ corresponds to a different $x$. After doing some analysis (which will be done in a later section), one can figure out that there are about $540,000$ pairs $(e,k)$ that can appear in the computation, and given $D=10^{\eta}$, the smallest feasible $Q$ is around $120$ when $\eta=1$, and it is even larger for larger values of $\eta$. Hence, we already need at least about $540,000\times 120\textrm{-bits}\approx 7.7$ MB just to store the lowest $Q$-bits of $m$. And that’s not even all we need, and we need to store $Q$ in addition to it. This is not acceptable.

Now the art is on how far we can compress this down. Indeed, there are several interesting features of the formula $\eqref{eq:core formula}$ we derived which together allow us to compactify this ridiculously large data into something much smaller. Let’s dig into them one by one.

(a) It is $k$ that matters, not $e$.

Recall that we have

\[m = \left\lceil \frac{2^{Q}x}{D} \right\rceil = \left\lceil 2^{Q+e+k-\eta-1}\cdot 5^{k-\eta} \right\rceil,\]given $x = 2^{e+k-1}\cdot 5^{k}$ and $D=10^{\eta}$. Let’s for a while ignore the ceiling and pretend that it’s actually floor. Then what are the lowest $Q$-bits of the above integer?

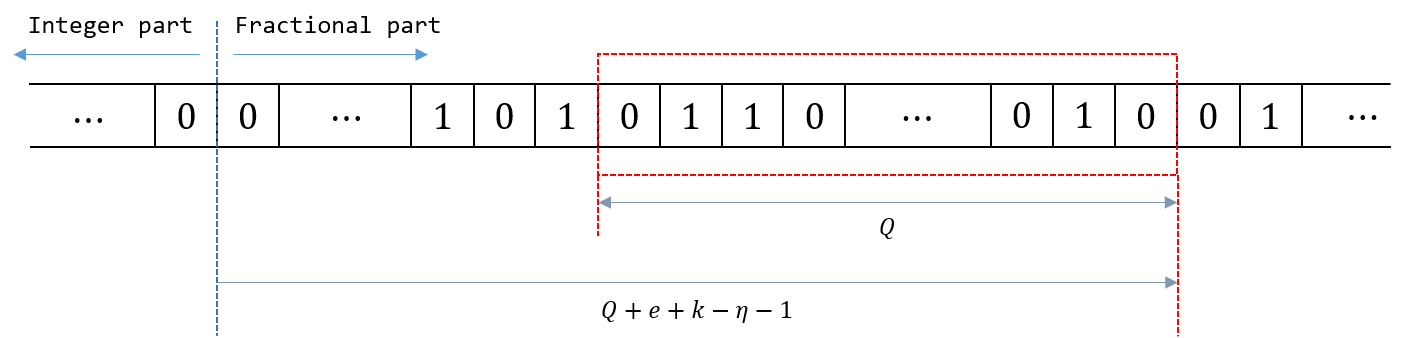

|

|---|

| Figure 1 - Bits of $5^{k-\eta}$ is shown in a row; bits in the window (red box) are the lowest $Q$-bits of $m$. The example shown is when $Q+e+k-\eta-1>0$. For the other case, the window will be on the left to the blue vertical line. |

Those are of course bits of $5^{k-\eta}$, starting (MSB) from the $(e+k-\eta)$-th bit, ending (LSB) at the $(Q+e+k-\eta-1)$-th bit. So for a fixed $k$, a different choice of $e$ corresponds to a different choice of the window (the red box in the figure). The starting (the left-most) position of the window is determined by $e$ (once $k$ and $\eta$ are fixed), and the size of the window is determined by $Q$. Note that those windows corresponding to $e$’s have a lot of intersection between them. This means that we do not need to store $m$ for each pair of $e$ and $k$. Rather, for each $k$, we just store sufficiently many bits of $5^{k-\eta}$, just enough to cover all possible windows we may need to look at. In other words, for all $e$’s such that the pair $(e,k)$ is relevant (that is, can appear), we take the union of all the windows corresponding to those $e$’s to get a single large window, and then we store the bits inside that window.

Often, the resulting large window may contain some leading zeros, which we can remove to further reduce the amount of information that needs to be stored. This means that when we load the necessary bits from the cache table at runtime, the window corresponding to the given $e$ may go beyond the range of bits we actually have in the table. But in this case we can simply fill in those missing bits with zeros.

Now, let’s not forget that we need the ceiling rather than the floor, but this is not a tremendous issue because we can easily compute the ceiling from the floor just by checking if $2^{Q+e+k-\eta-1}\cdot 5^{k-\eta}$ is an integer, which is just a matter of inspecting the inequalities

\[Q+e+k-\eta-1 \geq 0\quad\textrm{and}\quad k-\eta \geq 0.\](b) We need only one $k$ per $\eta$-many $k$’s.

Since we work with segments consisting of $\eta$ digits rather than individual digits, we do not need to consider all $k$’s. Instead, we choose a small enough $k_{\min}$ and only consider $k_{\min}$, $k_{\min} + \eta$, $k_{\min} + 2\eta$, $\cdots$, up to a large enough $k_{\min} + s\eta$. Hence, roughly speaking, choosing a big $\eta$ can result in a reduction in the size of the table by a factor of $\eta$.

(c) We don’t need to remember the smallest $Q$.

Recall that we not only need to store $m$ but also $Q$, which adds a non-negligible amount of static data. However, we do not actually need to precisely know the smallest $Q$ that does the job. More specifically, the $Q$ we use to compute the $m$ that we store in the table does not need to match the actual $Q$ we use at runtime, as long as the actual $Q$ we use at runtime is greater than or equal to the $Q$ we use for building the table.

What I mean is this. When we compute $m$ stored in the table, we want to find the minimum possible $Q$ that works, so that the window we get will be of the smallest possible size. However, it is okay to use a larger window at runtime if we want. To see why, recall that the left-most position of the window is not dependent on $Q$. Using a different $Q$ just changes the size of the window. Now, let $Q$ be the one that we used for building the table, and let $Q’$ be any integer with $Q’\geq Q$. Let $m’$ be what we will end up with if we try to load $Q’$-bits from the table instead of $Q$-bits, then we have

\[m' = \left\lceil\frac{2^{Q''}x}{D}\right\rceil 2^{Q'-Q''}\]for some \(Q\leq Q''\leq Q'\). Here we are assuming that, if the window of size $Q’$ goes beyond the right limit of the stored bits (which can occur since $Q’$ is chosen to be bigger than $Q$), then we fill in the missing bits with zeros, and also we perform the ceiling at the last bit we loaded from the cache. This is why we get this additional $Q’’$. Note that, however, this $Q’’$ is guaranteed to be between $Q$ and $Q’$ due to the construction of the cache table. Then the corresponding $\xi’$ is now given as

\[\xi' = \frac{m'D}{2^{Q'}} = \frac{\left\lceil 2^{Q''}x/D \right\rceil}{2^{Q''}}.\]Now since

\[m\cdot 2^{Q''-Q} = \left\lceil\frac{2^{Q}x}{D}\right\rceil 2^{Q''-Q} \geq \frac{2^{Q''}x}{D}\]holds and the left-hand side is an integer, it follows that

\[m\cdot 2^{Q''-Q} \geq \left\lceil \frac{2^{Q''}x}{D} \right\rceil\]holds, thus we get $\xi\geq \xi’$. This means that $\xi’$ still satisfies the conditions listed in Theorem 4.2, thus the formula

\[\left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right) = \left\lfloor \frac{\left(n(m'\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q'})\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q'}\right)D}{2^{Q'}} \right\rfloor\]is still valid.

This analysis leads us to two strategies for reducing the number of bits we need to store the values of $Q$:

Find the maximum among all the smallest $Q$’s for relevant $(e,k)$-pairs. Then at runtime, we will use this maximum $Q$ for all $(e,k)$. In this case, we do not need to store $Q$’s at all since it is a constant.

Alternatively, we can partition the set of $(e,k)$-pairs into groups which share a single $Q$, which is the largest of all the smallest $Q$’s for each member of the group. One way to make such a partition is to fix a positive integer $\ell$ (which we will refer as the collapse factor), and group all $(e,k)$-pairs that share the same $k$ and the same quotient $\left\lfloor (e-e_{\min})/\ell \right\rfloor$. In this way, we can reduce the number of bits needed to store $Q$’s roughly by a factor of $\ell$. In addition to that, we may store $\left\lceil Q/64 \right\rceil$ instead of $Q$ and use $\left\lceil Q/64\right\rceil\cdot 64$ instead of $Q$, because (assuming a $64$-bit platform) it is the number of $64$-bit blocks, rather than the number of bits, which determines the amount of computation we need to perform. For example, there is no benefit of choosing $Q=125$ over choosing $Q=128$, so we just use $Q=128$ in that case. This then also reduces the required number of bits by a certain factor.

In practice, having $Q$ as a fixed constant seems to allow the compiler to perform many aggressive optimizations, so the advantage of the second strategy is only apparent when the values of $Q$ for different $x$’s vary significantly.

Decimal digit generation

In the last section, we have discussed when it is allowed to use the formula $\eqref{eq:core formula}$:

\[\left(\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right) = \left\lfloor \frac{\left(n(m\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right)D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor.\]In this section, we will discuss how to actually leverage this formula to quickly compute decimal digits of $w = n\cdot 2^{e-1}$. For convenience, we will use the notation $m$ to really mean $(m\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})$ in this section.

Let us recall what operations we need to do for computing the above.

First, we need to multiply $n$, which is of $64$-bits (it is a bit smaller than that, but that doesn’t matter a lot in this case), and $m$, which is of $Q$-bits. We only take the lowest $Q$-bits from the result.

Next, we multiply the resulting $Q$-bit number with $D=10^{\eta}$. $D$ fits in $64$-bits if $\eta\leq 19$. In this case, we discard the lowest $Q$-bits and only take the higher bits.

Note that since $Q$ can be bigger than $64$, this inevitably involves some form of big integer arithmetic. Obviously, the required bit-width of this big integer arithmetic increases (which means that the computation will take more time) as $Q$ grows. In general, if we choose a larger $\eta$, then $Q$ gets bigger as well. Thus we have a space-time trade off here, because taking a larger $\eta$ makes the size of the table smaller.

When $\eta=1$, the maximum of all $Q$’s is about $120$, which means that the multiplications involved are between a $128$-bit integer and a $64$-bit integer. When $2\leq\eta\leq 19$, the maximum of all $Q$’s lies in between $129$ and $192$, which means that we need multiplications of a $192$-bit integer and a $64$-bit integer.

We will not seriously consider $\eta=1$ case, because it not only requires ridiculously big table size ($70$ KB, even after all the compression schemes explained in the last section) but also has terrible performance, as we have to perform two $128$-bit $\times$ $64$-bit multiplications for each single digit.

When $20\leq \eta\leq 22$, $Q$ is still at most $192$, but now $D=10^{\eta}$ cannot fit inside $64$-bits. Thus one may think that probably $\eta=19$ is the best choice. However, it turns out that $20\leq \eta\leq 22$ is also quite a sensible choice as well, because there is an elegant way of extracting the digits from $\eqref{eq:core formula}$, which basically works for any $\eta$: we don’t compute all of the digits at once, rather, we extract a smaller sequence of digits iteratively, from left to right.

What happens here is really no different from what James Anhalt’s algorithm does. If we want to know the first $\gamma_{1}<\eta$ decimal digits of \(\left\lfloor \frac{(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor,\) then we compute \(\left\lfloor \frac{(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})d_{1}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor\) with $d_{1} = 10^{\gamma_{1}}$. If we want to know the next $\gamma_{2}$ digits, then compute \(\left\lfloor \frac{(nmd_{1}\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})d_{2}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor\) with $d_{2} = 10^{\gamma_{2}}$, and for the next $\gamma_{3}$ digits, compute \(\left\lfloor \frac{(nmd_{1}d_{2}\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})d_{3}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor\) with $d_{3} = 10^{\gamma_{3}}$, and so on, until we exhaust all $\eta$ digits. And this procedure can be nicely iterated: at each iteration, we have a $Q$-bit number stored in a buffer, and we multiply $d=10^{\gamma}$ to it. The right-most $Q$ bits of the result will be stored back into the buffer for the next iteration, and the remaining left-most bits are the output of the current iteration.

This iteration approach allows for quite efficient computation of decimal digits in terms of the required number of multiplications. As an illustration, let us compare the required number of multiplications for the case $\eta=22$, $Q=192$ with the case of Ryū-printf. As in my Dragonbox paper, let us call $64$-bit $\times$ $64$-bit $\to 128$-bit multiplication as the full multiplication, and $64$-bit $\times$ $64$-bit $\to 64$-bit multiplication (i.e., taking only the lower half of the result) as the half multiplication. The point of distinguishing these two is that they have quite different performance characteristics in typical x64 machines. Or, in other machines often there is no direct instruction for doing the full multiplication, and we have to emulate it with multiple half multiplications. So generally full multiplications tend to be slower than half multiplications. Now let us analyze the number of full/half multiplications we need to perform.

In our iteration scheme, first we have to prepare the $Q$-bit number $(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})$, which means we multiply a $64$-bit integer $n$ with a $192$-bit integer $m$, where we only take the lowest $192$-bits from the result. This requires $2$ full multiplications and $1$ half multiplication. Next, we extract $16$ decimal digits (as a $64$-bit integer) from the segment by multiplying $10^{16}$. This requires $3$ full multiplications. And then, we divide this into two $8$-digits chunks (so that each of them fits in $32$-bits), which means that we divide it by $10^{8}$ and take the quotient and the remainder. This requires $1$ full multiplication and $1$ half multiplication, by applying the usual trick of turning a constant division into a multiplication followed by a shift. Next, we extract the remaining $6$ digits (as a $32$-bit integer) from our $22$-digits segment, which again requires $3$ full multiplications. At this point, we performed $9$ full multiplications and $2$ half multiplications to get three $32$-bit chunks (which I call subsegments) each consisting of $8$, $8$, and $6$ digits. Then, using James Anhalt’s algorithm, we need $4+4+3=11$ half multiplications for printing out all of them. Thus in total, we need $9$ full multiplications and $13$ half multiplications.

On the other hand, in Ryū-printf, we first multiply a $64$-bit integer to a $192$-bit cache entry, extract the upper $128$-bits from the result, shift it by a certain amount, divide it by $10^{9}$ and then take the remainder, to get a segment consisting of $9$ decimal digits. The first step of multiplying a $64$-bit integer and a $192$-bit integer requires $3$ full multiplications. Applying the usual trick, we can turn the division by $10^{9}$ into a multiplication, and in this case since the dividend is of $128$-bits, the magic number we use for multiplication is also of $128$-bits. More precisely, we need to multiply two $128$-bit integers, and then take the second $64$-bit block from the resulting $256$-bit integer. This requires $3$ full multiplications and $1$ half multiplication. Next, to compute the remainder from the quotient, we need $1$ half multiplication (in $32$-bits). So we need to perform $6$ full multiplications and $2$ half multiplications to get a $32$-bit chunk consisting of $9$ digits. Then, again using James Anhalt’s algorithm, we need $5$ half multiplication for printing these $9$ digits out. Therefore, we need $6$ full multiplications and $7$ half multiplications in total.

Hence, in average, our scheme requires $9/22\approx 0.4$ full multiplications and $13/22\approx 0.6$ half multiplications per a digit, while Ryū-printf requires $6/9\approx 0.7$ full multiplications and $7/9\approx 0.8$ half multiplications per a digit, which means that our scheme is like $60$ % better throughput compared to Ryū-printf, in terms of the required number of full multiplications, and $30$ % better in terms of half multiplications.

The throughput for $\eta=18$, $Q=192$ is even better. Preparation of $(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})$ again requires $2$ full multiplications and $1$ half multiplication, and we extract all of $18$ digits at once (as a $64$-bit integer) by performing $3$ full multiplication. Splitting it into two $9$-digits subsegments requires $1$ full multiplication and $1$ half multiplication, and printing them out requires $5+5=10$ half multiplications. So in total, we need $6$ full multiplications and $12$ half multiplications, or $6/18\approx 0.3$ full multiplications and $12/18\approx 0.7$ half multiplications per a digit.

Which $(e,k)$-pairs are relevant?

So far, we have mentioned “a relevant $(e,k)$-pair” (or alike) a lot but not really precisely defined what it means. So let’s talk about it.

Recall that we are trying to compute decimal digits of $w=n\cdot 2^{e-1}$. The way we do it is to compute $\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$ with $D=10^{\eta}$. Note that, if $k$ is too large, then $w\cdot 10^{k}$ will always be an integer multiple of $D=10^{\eta}$, because $2$ is a divisor of $10$. Then we always get $\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)=0$, which means that we do not ever need to consider such a large $k$. Specifically, for given $e$, this always happens regardless of $n$ if:

- $k\geq \eta$ when $e-1\geq0$, and

- $k\geq \eta-e+1$ when $e-1<0$.

Hence, for given $k$, the pair $(e,k)$ is “relevant” only when $k\leq \eta-1$ if $e-1\geq 0$ and $k\leq\eta-e$ when $e-1<0$. In particular, we never need to consider a $k$ such that $k\geq \eta - e_{\min} + 1$ where $e_{\min}=-1074$.

How about the other side? Given $e$, finding the smallest $k$ such that $(e,k)$ is relevant means to find the position of the first nonzero decimal digit of $w = n\cdot 2^{e-1}$, for the range of $n$ given. In fact, we already know how to do it. In the Dragonbox paper, we showed that it is possible to reliably compute $\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\rfloor$ for $k=\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor$ for $\kappa=2$ (or $\kappa=1$ for IEEE-754 binary32) by multiplying (an appropriate shift of) $n$ to the $k$-th table entry of the Dragonbox algorithm. Here, we are not taking $\mathrm{mod}\ D$, so there is no further digit we can extract by considering a smaller $k$. Therefore, this $\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor$ is the first segment that we ever need to look at.

The choice $k = \kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor$ guarantees that this first segment is always nonzero. Indeed, it must contain at least $3$ decimal digits, because

\[\begin{align*} w\cdot 10^{k} &= n\cdot 2^{e-1}\cdot 10^{k} \\ &\geq 2^{e}\cdot 10^{\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor} \\ &\geq 2^{e}\cdot 10^{\kappa - e\log_{10}2} \\ &= 10^{\kappa} \end{align*}\]where the right-hand side is of $(\kappa+1)$-digits. In fact, if $w$ is not a subnormal number, we have $n\geq 2^{53}$, so

\[\begin{align*} w\cdot 10^{k} &= n\cdot 2^{e-1}\cdot 10^{k} \\ &\geq 2^{52}\cdot 2^{e}\cdot 10^{\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor} \\ &\geq 2^{52}\cdot 10^{\kappa}, \end{align*}\]which means that $\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor$ must be of at least $18$-digits. On the other hand, we know $n\leq 2^{54}-1$, so

\[\begin{align*} w\cdot 10^{k} &= n\cdot 2^{e-1}\cdot 10^{k} \\ &\leq (2^{54}-1)\cdot 2^{e-1}\cdot 10^{\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor} \\ &< \left(2^{53}-\frac{1}{2}\right)\cdot 2^{e}\cdot 10^{\kappa - e\log_{10}2 + 1} \\ &= \left(2^{53}-\frac{1}{2}\right)\cdot 10^{\kappa+1}, \end{align*}\]so $\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor$ must be of at most $19$-digits.

So, (with the exception of the case of subnormal numbers) this $64$-bit integer $\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor$ already gives us a pretty large number of digits of $w$, which means that we have already (mostly) solved the common case, i.e., the small precision case, of our problem at hand.

(Note that it is also possible to always extract $18\sim 19$ digits even from subnormal numbers by normalizing $w$, that is, by multiplying an appropriate power of $2$ to $n$ and subtracting the corresponding power from $e$. That requires a bit more table entries than the ones we used for Dragonbox though. Whether or not this is a good thing to do is not very clear to me at this point. The current implementation does not do normalization.)

Therefore, the pair $(e,k)$ is “relevant” only when $k$ is large enough so that computing

\[\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right) = \left(\left\lfloor n\cdot 2^{e+k-1}\cdot 5^{k}\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)\]can produce at least one digit that is not contained in the first segment, which means that

\[k \geq \kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor + 1\]holds.

Therefore, for given $k$,

When $0\leq e-1\leq e_{\max}-1 = 970$, $(e,k)$ is relevant if and only if

\[\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor + 1 \leq k \leq \eta-1.\]When $-1075 = e_{\min}-1 \leq e-1<0$, $(e,k)$ is relevant if and only if

\[\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor + 1 \leq k \leq \eta-e.\]

Recall that we will only consider $k$’s of the form $k = k_{\min} + s\eta$. Let us call the integer $s=0,1,2,\ \cdots\ $ the multiplier index. Once $k_{\min}$ has been chosen, the greatest multiplier index $s_{\max}$ can be figured out by finding the largest $s_{\max}$ satisfying the inequality

\[k_{\min} + s_{\max}\eta \leq \eta - e_{\min}\]with $e_{\min}=-1074$, or equivalently,

\[s_{\max} = \left\lfloor \frac{\eta - e_{\min} - k_{\min}}{\eta}\right\rfloor.\]To choose $k_{\min}$, note that it is enough to chose $k_{\min}$ such that when $e=e_{\max}$, $\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k_{\min}}\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$ contains the first digit that cannot be obtained from the first segment. Since we extract $\eta$-digits at once, this means that

\[k_{\min} \leq \kappa - \left\lfloor e_{\max}\log_{10}2\right\rfloor + \eta\]with $e_{\max} = 971$ is satisfied. No smaller $k$ ever needs to be considered.

In general, choosing a smaller $k_{\min}$ gives larger $s_{\max}$ so more powers of $5$ to be stored in the table, so we would want take the largest possible $k_{\min}$, that is $k_{\min} = \kappa - \left\lfloor e_{\max}\log_{10}2\right\rfloor + \eta$. However, it turns out that choosing a little bit smaller $k_{\min}$ can actually make the table a little bit smaller. In the implementation, I did some trial-and-error type experiments to find the optimal $k_{\min}$ that minimizes the table size.

In this way, we can determine for which $k$ the bits of $5^{k-\eta}$ need to be stored in the cache table.

For given $e$, the first multiplier index, which gives the first digit that cannot be obtained from the first segment, can be obtained by finding the smallest $s$ satisfying

\[k = k_{\min} + s\eta \geq \kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor + 1,\]or equivalently,

\[s = \left\lceil \frac{(\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor) - k_{\min} + 1}{\eta} \right\rceil = \left\lfloor \frac{(\kappa - \left\lfloor e\log_{10}2\right\rfloor) - k_{\min} + \eta}{\eta} \right\rfloor.\]The cache table

At this point, almost all of the whole algorithm has been explained. In this section, I collected some missing details that are needed to actually build the cache table.

(a) How do we arrange the computed bits of $5^{k-\eta}$ in the memory?

For each multiplier index $s=0,\ \cdots\ ,s_{\max}$, we find all the necessary bits of $5^{k-\eta}$ with $k=k_{\min}+s\eta$. After cutting off all leading zeros, we simply stitch all of these bits together and store them in an array of $64$-bit integers. In theory, the first bit for each $k$ in this case will always be $1$, so we can even remove those bits, but let’s not do that as it will complicate the implementation a lot for a marginal benefit.

(b) How to locate the necessary bits from the table, for given $e$ and $k$?

For each multiplier index $s$, we store needed metadata. There are three different kinds of information in this metadata.

First, we store the position of the first stored bit of $5^{k-\eta}$ in the cache table.

Second, we store the offset value which, when added with the exponent $e$, yields the position of the first needed bit of $5^{k-\eta}$ from the table for given $e$, or in other words, the starting position of the window. Since the window shifts to right by $1$ if we increase $e$ by $1$, such an offset value is enough for determining the position. Note that this starting position of the window can go further to the left limit of the stored bits because we removed all the leading zeros.

(This in particular means that the offset value can be negative. In the implementation, thus I shifted all of these offset values by some amount to make everything nonnegative. My intention was that by doing so we can possibly use a smaller unsigned integer type for storing those offsets. In the end the size of the integer type wasn’t affected but I left it as it is.)

Finally, we also need a similar offset for the $Q$-table, defined to be the unique value which, when added with $\left\lfloor \frac{e-e_{\min}}{\ell}\right\rfloor$ yields the index in the $Q$-table. This information is only needed when we use the collapse factor $\ell$ for compressing $Q$’s, and is not needed if we use a fixed constant $Q$.

Summary of how it works

Here is how the algorithm works in a nutshell:

Precompute powers of $5$ up to the necessary precision and store them.

Convert the given floating-point number into a “fixed-point form” by multiplying appropriate bits loaded from those precomputed powers of $5$ into the significand of the input.

Iteratively extract the digits from the computed fixed-point form, just like James Anhalt’s algorithm.

And here is a little bit more detailed version of the summary:

Given a floating point number $w = n\cdot 2^{e-1}$, we want to compute $\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k} \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{\eta}\right)$ for some $k$’s.

For the first several digits, we can just multiply an appropriate entry from the Dragonbox table, or anything like that will work.

To prepare for the case when that will not yield sufficiently many digits, we find $Q$ that makes the equality \(\begin{align*} \left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k} \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{\eta}\right) &= \left(\left\lfloor n\cdot (2^{e+k-1}\cdot 5^{k}) \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{\eta}\right) \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{(n\left\lceil 2^{Q+e+k-\eta-1}\cdot 5^{k-\eta} \right\rceil \ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})\cdot 10^{\eta}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor \end{align*}\) to hold for all $n$ using Theorem 4.2, for all relevant $(e,k)$-pairs.

For each $k$, find the range of bits of $5^{k-\eta}$ that appears in \(\left\lfloor 2^{Q+e+k-\eta-1}\cdot 5^{k-\eta} \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\) for all $e$ such that $(e,k)$ is one of the pairs considered in the previous step.

Compute those bits and store them in a static data table, possibly along with $Q$’s.

At runtime, for given $e$ and $k$ we choose the needed bits from the table and compute \(\left(n\left(\left\lceil 2^{Q+e+k-\eta-1}\cdot 5^{k-\eta} \right\rceil \ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right)\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q}\right).\)

By iteratively multiplying a power of $10$ and taking the upper bits, we can compute the digits of $\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k} \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{\eta}\right)$ from left to right.

Rounding

After generating the requested number of digits, we have to perform rounding. It sounds simple, but it is in fact an incredibly complicated issue. The root cause of the difficulty is the many ramifications of different cases that all need different handling. However, fortunately, most of those cases can be categorized into two which we will explore in this section.

Rounding inside a subsegment

A segment, which consists of $\eta$-digits, is divided into several subsegments that are small enough to fit inside $32$-bits. The most common case of rounding is when it happens inside a subsegment.

Let’s say we have a $9$-digit subsegment, and we need to round at the $t$-th digit of the subsegment for some $1\leq t\leq 8$. So there are at least one digit left in the subsegment that will not be printed. In this case, the rounding happens when the following conditions are met, assuming the default rounding rule:

If the remaining $(9-t)$-digits consist a number that is strictly bigger than $10^{9-t}/2$, then round-up.

If that number is strictly smaller than $10^{9-t}/2$, then round-down.

When that number is exactly $10^{9-t}/2$, then:

- If the currently printed number is odd, then round-up.

- If there are further nonzero digits after the current subsegment, then round-up.

- Otherwise, round-down.

The problem is that $t$ is in general a runtime variable, not a constant. So it sounds like we have to compute this $(9-t)$-digits number at runtime. But it turns out, we can still do this check without computing it.

The idea is again based on the “fixed-point fractions trick” I learned from James Anhalt’s algorithm. It goes as follows.

Let’s say we have a $9$-digit subsegment. Let’s call it $n$ (this $n$ has nothing to do with the $n$ we have been using in previous sections). In order to print $n$, we find a good approximation of the rational number $n/10^{8}$ as a $64$-bit fixed-point fractional number, where the upper $32$-bits represent the integer part and the lower $32$-bits represent the fractional part. More precisely, we find a $64$-bit integer $y$ such that

\[\frac{2^{32}n}{10^{8}} \leq y < \frac{2^{32}(n+1)}{10^{8}}.\]holds. (See the previous post for details.)

The first digit of $n$ can then be obtained as $\left\lfloor\frac{y}{2^{32}}\right\rfloor$. Also the next $(t-1)$-digits can be obtained by multiplying $10^{t-1}$ to the lower $32$-bits of $y$ and extracting the upper $32$-bits from the result. We assume that we already have done this to print $t$-digits from $n$. Let us call the remaining lower half of the result $y_{1}$.

Then the remaining $(9-t)$-digits can be obtained from $y_{1}$ by multiplying $10^{9-t}$ to it and then extracting the upper $32$-bits. But the thing is, we don’t need to precisely know these digits. All we want to do is to compare those digits with $10^{9-t}/2$. Note that, with $k=9-t$,

\[\left\lfloor \frac{y_{1}\cdot 10^{k}}{2^{32}}\right\rfloor \geq 10^{k}/2\]holds if and only if $y_{1} \geq 2^{31}$, if and only if the MSB of $y_{1}$ is $1$. Hence, we round-down if the MSB is $0$.

However, we cannot be sure what to do if the MSB is $1$, because that can mean either the equality or the strict inequality. To distinguish those two cases, we have to inspect the inequality

\[\left\lfloor \frac{y_{1}\cdot 10^{k}}{2^{32}}\right\rfloor \geq \frac{10^{k}}{2} + 1,\]which is equivalent to

\[y_{1} \geq 2^{31} + \frac{2^{32}}{10^{k}}, \quad\textrm{or}\quad y_{1} \geq \left\lceil 2^{31} + \frac{2^{32}}{10^{k}}\right\rceil.\]The right-hand side is not a constant since $k$ is a runtime variable, but we can simply store all possible values of it in yet another precomputed static table and then index it with $k-1$ (note that $k$ cannot be zero).

Still, we may need to check if there are further nonzero digits left after ths current subsegment. I will not go into details of this since it is a sort of a massive case-by-case thing, but overall the idea is that this is just the matter of doing the integer-check of a number of the form $n\cdot 2^{e+k-e_{0}}\cdot 5^{k-k_{0}}$ (this $n$ is the $n$ from previous sections), which then is just the matter of counting factors of $2$ and $5$ inside $n$.

Rounding at the subsegment boundary

The above doesn’t work for $t=9$ since there is no more digit at all to inspect. To obtain further digits we have to look at the next subsegment. But that is not strictly needed: we only need to know just one more bit. Suppose that the current subsegment is equal to $\left(\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{9}\right)$ for some $k$ (this $k$ is a different $k$ from previous sections because $k-k_{\min}$ in this case does not need to be a multiple of $\eta$), then this means that we need to know the first fractional bit of the rational number $w\cdot 10^{k}$. Assume that we were able to get this bit upfront. Then the rounding conditions can be checked as follows:

If the next bit is $0$, then round-down.

If the next bit is $1$ and the last digit printed is odd, then round-up.

If the next bit is $1$ and if there is at least one nonzero fractional bit of $w\cdot 10^{k}$ after that, then round-up.

Otherwise, round-down.

Checking if there are further nonzero bits is again the matter of counting factors of $2$ and $5$, so let us focus on how to get this one more additional bit. I will not go into all the details, but the core idea is this. Recall that we are computing the number

\[\left\lfloor nx \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D.\]If we want to compute one more bit than this, then what we do is to compute

\[\left\lfloor 2nx \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2D\]instead. Indeed, if $b$ is the first fractional bit of $nx$, then $\left\lfloor 2nx\right\rfloor = 2\left\lfloor nx\right\rfloor + b$, so

\[\begin{aligned} 2\left(\left\lfloor nx\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right) + b &= 2\left\lfloor nx\right\rfloor - 2D\left\lfloor\frac{\left\lfloor nx\right\rfloor}{D}\right\rfloor+b \\ &= \left\lfloor 2nx\right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{nx}{D}\right\rfloor 2D \\ &= \left\lfloor 2nx\right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{2nx}{2D}\right\rfloor 2D\\ &= \left\lfloor 2nx\right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{\left\lfloor 2nx\right\rfloor }{2D}\right\rfloor 2D\\ &= \left(\left\lfloor 2nx \right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2D\right). \end{aligned}\]Thus, $b$ can be obtained by inspecting the last bit of the right-hand side, and the remaining bits precisely constitute the value of $\left(\left\lfloor nx\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ D\right)$.

Now, suppose that $2\xi = \frac{2mD}{2^{Q}}$ is a good enough approximation of $2x$ in the sense that the conditions of Theorem 4.2, when $x$ is replaced by $2x$ and $\xi$ is replaced by $2\xi$, are satisfied, then we obtain

\[\begin{aligned} \left(\left\lfloor 2nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 2D\right) &= \left\lfloor 2nx \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{\left\lfloor 2nx \right\rfloor}{2D} \right\rfloor 2D \\ &= \left\lfloor 2n\xi \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{\left\lfloor 2n\xi \right\rfloor}{2D} \right\rfloor 2D \\ &= \left\lfloor 2n\xi \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor\frac{n\xi}{D} \right\rfloor 2D \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{2nmD}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor - \left\lfloor \frac{nm}{2^{Q}}\right\rfloor 2D \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{2nmD - \lfloor nm/2^{Q} \rfloor 2D\cdot 2^{Q}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{(nm - \lfloor nm/2^{Q} \rfloor 2^{Q})2D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor \\ &= \left\lfloor \frac{(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})2D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor. \end{aligned}\]So, in this case the additional bit can be simply obtained by multiplying $2D$ instead of $D$ to $(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})$, without changing anything else.

In order to make this computation valid, we need to have the inequality

\[2\xi = \frac{\left\lceil 2^{Q}x/D\right\rceil 2D}{2^{Q}} < \begin{cases} 2x + \frac{1}{\tilde{v}\tilde{q}} & \textrm{if $2x=\frac{\tilde{p}}{\tilde{q}}$ is rational with $\tilde{q}\leq n_{\max}$},\\ \frac{\tilde{p}^{*}}{\tilde{q}^{*}} & \textrm{otherwise} \end{cases}\]instead of $\eqref{eq:core inequality}$, where things with $\tilde{\cdot}$ denote what we obtain from the corresponding things without $\tilde{\cdot}$ when we replace $x$ by $2x$. The above inequality in general is a little bit stricter than $\eqref{eq:core inequality}$, so in fact we have to use this instead of $\eqref{eq:core inequality}$ for computing $m$’s and $Q$’s if we want to ensure correct rounding.. Roughly speaking, replacing $\eqref{eq:core inequality}$ by the above increases $Q$ by $1$ overall, but fortunately this does not radically change any discussion we have done so far.

Now, suppose we have

\[\left(\left\lfloor 2nx \right\rfloor \ \mathrm{mod}\ 2D\right) = \left\lfloor \frac{(nm\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})2D}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor.\]Assume that we already have extracted $\gamma_{1}$-digits from it so that we have

\[(nmd_{1}\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})\]as the iteration state where $d_{1} = 10^{\gamma_{1}}$, and our current subsegment is the next $\gamma_{2}$-digits, which means that it can be obtained as

\[\left\lfloor \frac{(nmd_{1}\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})d_{2}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor\]with $d_{2}=10^{\gamma_{2}}$. Then, to obtain one more bit, we simply compute

\[\left\lfloor \frac{(nmd_{1}\ \mathrm{mod}\ 2^{Q})2d_{2}}{2^{Q}} \right\rfloor\]instead. The needed bit is then the last bit of the above, while the remaining bits constitute the actual subsegment.

Actual implementation

Here is an actual implementation. You can have some quick experiment with it here.

In the implementation, several different cache tables are prepared. The table used for computing the first segment is called the main cache table, which is consisting of the same entries as in Dragonbox. The one used for further digits is called the extended cache table. The implementation allows the users to choose which specific tables for each of those two.

There are two main cache tables, just like the Dragonbox implementation, the full table and the compressed table, each consisting of $9904$ bytes and $584$ bytes.

There are three extended cache tables:

the long extended cache table, consisting of $3680$ bytes, generated with the segment length $\eta=22$ assuming constant $Q=192$,

the compact extended cache table, consisting of $1212$ bytes, generated with the segment length $\eta=80$ and the collapse factor $\ell=64$, and

the super-compact extended cache table, consisting of $580$ bytes, generated with the segment length $\eta=252$ and the collapse factor $\ell=128$.

The implementation currently does not support the compact table.

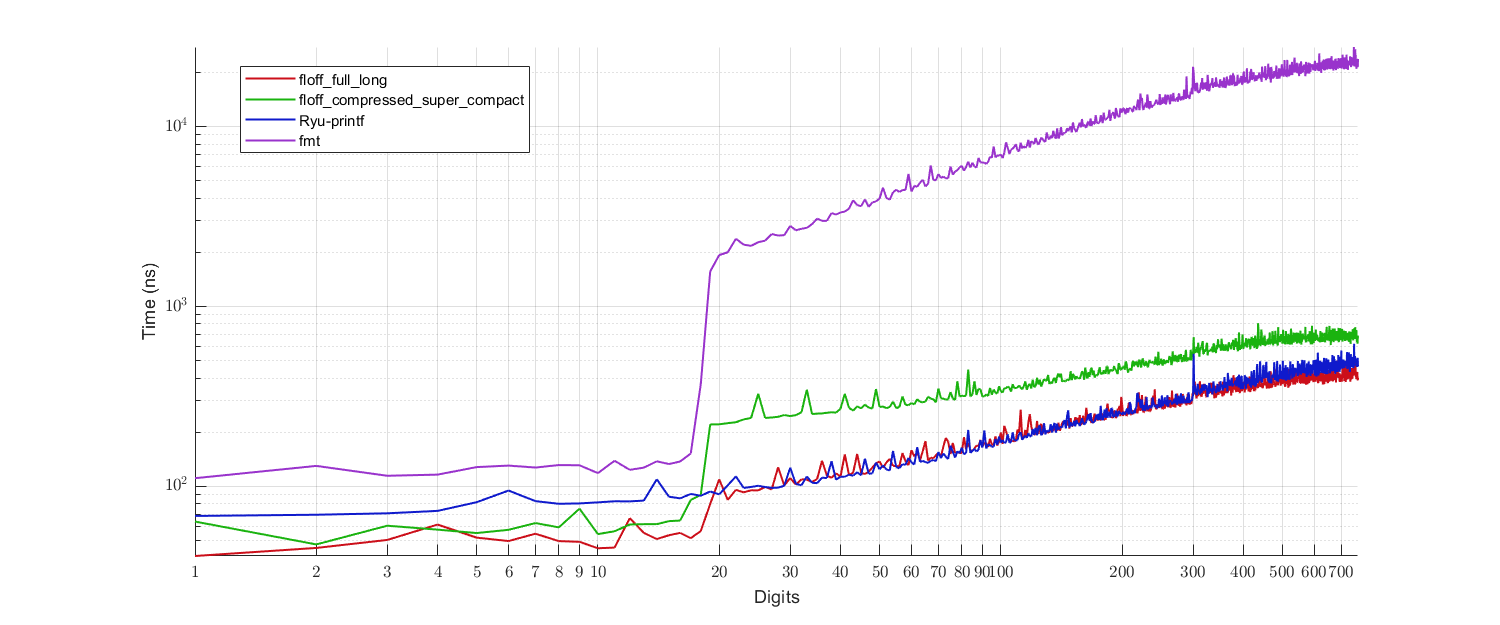

And here is how it performs:

|

|---|

| Figure 2 - Performance benchmark. |

- Red: Proposed algorithm with the full ($9904$ bytes) cache table and the long ($3680$ bytes) extended cache table.

- Green: Proposed algorithm with the compressed ($584$ bytes) cache table and the super-compact ($580$ bytes) extended cache table.

- Blue: Ryū-printf (reference implementation).

- Purple:

fmtlib(a variant of Grisu3 with Dragon4 fallback).

So, the proposed algorithm performs:

- Better than Ryū-printf for the small digits case, which is mostly covered by the main cache table,

- Comparable to Ryū-printf for the large digits case, when supplied with the long extended cache,

- Worse than Ryū-printf but significantly faster than

fmtlib(Dragon4) for the large digits case, when supplied with the super-compact extended cache.

WARNING

The implementation has NEVER been polished for real-world usage. Especially, I have NOT done any fair amount of formal testing of this implementation. Furthermore, the code is ultra-messy and is full of almost-same-but-slightly-different copies of same code blocks, which is a perfect recipe for bugs.

I’m pretty confident about the correctness of the algorithm itself though. I believe that any error is likely due to some careless mistakes rather than some fundamental issue in the algorithm.

Possible performance issues of the algorithm

Now, let’s talk about some problematic aspects of our algorithm which can result in bad performance.

Deep hierarchy

Taking large segment length $\eta$ (e.g. $\eta=22$) is a great way to reduce the size of the table, but it has a cost: it introduces deep levels of hierarchy. Let me elaborate what I mean by that.

As pointed out in the previous post, the common wisdom for printing integers is to work with two digits at a time, rather than one. So when we print integers we basically split the input integer into pairs of digits. This introduces one level of hierarchy: individual digits and pairs of digits. Recall also from the previous post that, when we are working with $64$-bit integers rather than $32$-bit integers, it is beneficial to split the $64$-bit input into several $32$-bit chunks, because usually $32$-bit math is cheaper. This introduces another level of hierarchy: individual digits, pairs of digits, and groups of pairs of digits fitting into $32$-bits.

Now, if $\eta$ is bigger than $9$, we cannot store the whole segment into $32$-bits, and if $\eta$ is bigger than $19$, even $64$-bits are insufficient. For $\eta=22$, we need at least three $32$-bit subsegments. For example, we split a segment into two $8$-digits subsegments and one $6$-digits subsegment. Note that getting a subsegment from a segment, following the method explained in the Decimal digit generation section, requires $Q$-bit math which is much more expensive than $64$-bit math. So we do not repeat the iteration $3$ times, rather, we group two subsegments into a single $64$-bit integer, so we need only $2$ iterations and then we separate this $64$-bit integer into two subsegments (which involves $64$-bit math). And this introduces yet another level of hierarchy.

And the bottom-line is, hierarchy is bad in terms of the complexity of the actual implementation. It may introduce more branching, more code, and thus in particular more instruction cache pollution. Roughly speaking, introducing one more level of hierarchy is like converting a flat for loop into a nested loop. In our case it is actually worse than that because it complicates the rounding logic a lot.

In comparison, (the standard implementation of) Ryū-printf only involves more or less three levels of hierarchy: individual digits, pairs of digits, and $9$-digits segments. We could achieve the same depth of hierarchy by just choosing $\eta=9$, but that will of course bloat the size of the static table by the factor of approximately $22/9$. I’m suspecting that maybe choosing $\eta=18$ will be the sweet spot and results in the best performance, but I did not run an actual experiment.

Too much compression

In Ryū-printf, loading the required cache bits from the static table is a no-brainer once you have the index. You just load the table entry located at that index, job done. But our compression scheme complicates this procedure a lot. For example, our compression scheme mandates us to fill in missing leading and trailing bits with zero. Also, due to the compact bitwise packing, a $64$-bit block from the cache table may contain bits from multiple different powers of $5$, so we have to manually remove all the wrong bits “flooding” from adjacent powers of $5$. Also, we have to perform bitwise-shifts spanning multiple $64$-bit blocks, and the direction of shift can depend on the input. Due to all of these (and more), the algorithm consumes quite considerable amount of time for load the required bits from the table even before it actually starts multiplying them. And note that this is not a one-time cost, as we need to do this each time we need a new segment, thus it impacts the throughput quite a lot. Probably this is the reason why our implementation doesn’t show a clear win over Ryū-printf in terms of the throughput.

Again, by not applying many of our compression strategies (e.g. removing leading zeros), this complication can be relaxed as much as we want. But I decided to compress the table as much as possible at any cost of performance loss, because the small precision case is already mostly covered by the main cache table (the Dragonbox table) alone, and the extended table is essentially used only for pretty large precisions. Anyway, it’s worth noting that this is another place where there is a space-time trade-off.

Overlapping digits

Using two separate tables, one for first several digits and another for further digits, has an issue of possible overlapping digits. What happens here is that, for the first several digits, we basically select any $k$ that maximizes the number of digits we get at once. That is, we select $k$ such that $\left\lfloor w\cdot 10^{k}\right\rfloor$ is maximized while still fitting inside $64$-bits. This allows us to squeeze out $18\sim 19$ digits (for normal numbers, and possibly less for subnormal numbers). However, when we need further digits, we cannot select the right $k$ that will give us the $\eta$-digits that immediately follow the ones we got from the first segment, because we only store one power of $5$ per $\eta$ exponents. In the worst case scenario, the $k$ we select will give us only one new digit. Furthermore, the number of these “overlapping digits” between the first segment (which we get using the main cache table) and the second segment (which we get using the extended cache table) can vary depending on the input. However, this is again a price worth paying, because this separation of two tables allows us to compress the extended cache table as much as we want, while not compromising the performance for the small digits case.

Having to load/store

If we choose $Q$ to vary, then it somewhat mandates the access to the stored blocks in the digit generation procedure to be through the stack rather than registers. This is because there is usually no concept of “arrays” of registers, and it is not possible to dynamically index the registers. In theory, it should be possible to load the memory into the register only once and use it indefinitely because the maximum size of the array is fixed (and often small, say $3 = 192/64$). This means that the dynamic indexing could be converted into constant indexing plus some branching. However, this is complex enough that there may be no benefit in doing so, and no actual compiler seems to do something like this. This is why I chose a fixed constant $Q$ for $\eta=22$ in the implementation.

Conclusion

It is possible to achieve a comparable performance to Ryū-printf while having much smaller amount of static data. To be fair, I should say that the benchmark I’ve done is not quite fair, because the reference implementation of Ryū-printf does not do a lot of integer-formatting tricks I did for my implementation. I think the Ryū-printf implementation could be made a lot faster by doing so.

However, I would dare say that the proposed algorithm is overall just strictly superior, because the core formula behind it is simpler than the corresponding formula in Ryū-printf. Both formulae are more or less equally powerful in terms of their ability to compute $\left(\left\lfloor nx\right\rfloor\ \mathrm{mod}\ 10^{\eta}\right)$ for the same segment size $\eta$, but the formula for the proposed algorithm is simpler and requires less number of multiplications. If we give up many of the compression ideas given and adopt a similar approach to Ryū-printf, but use the core formula from the proposed algorithm instead, then I don’t doubt that the resulting algorithm would perform way better than Ryū-printf. However, I haven’t bothered to conduct this experiment because my main motivation was to develop an algorithm that only requires small cache table.

There are still tons of places where things can get further improved, and it would be interesting to see how it could be used to implement an arbitrary-precision floating-point parser in the future. I hope we can get there soon!

Appendix: Fixed-point fraction trick revisited

The implementation extensively relies on the fixed-point fraction trick explained in the previous post. Due to excessive variety of different combinations of the parameters, I felt obliged to give some more shots on it to come up with a better analysis. Here is what I got.

Fixed-length case

Here I describe a better analysis of the fixed-length case treated in the last section of the previous post. Recall that for given $n$, we want to find $y$ such that

\[\frac{2^{D}n}{10^{k}} \leq y < \frac{2^{D}(n+1)}{10^{k}}.\]First of all, why not generalize this a little bit:

\[\frac{np}{q} \leq y < \frac{(n+1)p}{q}.\]So our original problem is when $p = 2^{D-k}$ and $q=5^{k}$. We attempt to let

\[y = \left\lfloor\frac{nm}{2^{L}}\right\rfloor + 1\]and see if there is a possible choice of $m$ and $L$. Again, let’s generalize this a little bit and look at

\[y = \left\lfloor n\xi\right\rfloor + 1\]instead. (Note that these generalizations are not just for the sake of generalizations; the point is really to simplify the analysis by throwing away all the details that play little to no role in the core arguments.) Then the inequality we need to consider is

\[\label{eq:jeaiii fixed-length} \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{np}{q}\right\rceil - \frac{1}{n} \leq \xi < \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{(n+1)p}{q}\right\rceil - \frac{1}{n}.\]Hence, we need to maximize the left-hand side and minimize the right-hand side of the above inequality over the given range of $n$ to see if there is a feasible choice of $\xi$.

First, let us write

\[\left\lceil\frac{np}{q}\right\rceil = \frac{np}{q} + \frac{r}{q}\]where $0\leq r < q$ is an integer. Then the left-hand side of $\eqref{eq:jeaiii fixed-length}$ becomes

\[\frac{p}{q} - \frac{q - r}{nq}.\]Hence, we want to find $n$ that maximizes the above, or equivalently, minimizes

\[\frac{q-r}{n}.\]This minimization problem is almost equivalent to what’s done in the first case of Theorem 4.2. Indeed, we can apply the same proof idea here. Let $v$ be the greatest integer such that $vp\equiv 1\ (\mathrm{mod}\ q)$ and $v\leq n_{\max}$. We claim that $n=v$ is the minimizer of the above. Suppose not, then there exists $n\leq n_{\max}$ such that

\[\frac{q-r}{n} < \frac{1}{v}\]where $r$ is the smallest nonnegative integer such that $np\equiv -r\ (\mathrm{mod}\ q)$. Multiplying $nvp$ to both sides, we get

\[vp(q-r)< np.\]However, since both sides are congruent to $-r$ modular $q$, there should exist a positive integer $e$ such that

\[np = vp(q-r) + eq.\]Now, since $p,q$ are coprime and both $np$ and $vp(q-r)$ are multiples of $p$, it follows that $e$ is a multiple of $p$, so in particular $e\geq p$. Then we get

\[n = v(q-r) + (e/p)q \geq v + q.\]This in particular implies $v+q\leq n_{\max}$, but that contradicts to the definition of $v$. Hence, $v$ must be the minimizer.

As a result, we can rewrite $\eqref{eq:jeaiii fixed-length}$ as

\[\frac{p}{q} - \frac{1}{vq} \leq \xi < \frac{1}{n}\left\lceil\frac{(n+1)p}{q}\right\rceil - \frac{1}{n}.\]For the right-hand side, note that

\[\frac{(n+1)p}{q} = \frac{np}{q} + \frac{p}{q} = \left\lceil\frac{np}{q}\right\rceil + \frac{p - r}{q},\]so

\[\left\lceil \frac{(n+1)p}{q}\right\rceil = \left\lceil\frac{np}{q}\right\rceil + \left\lceil \frac{p - r}{q} \right\rceil = \frac{np}{q} + \frac{r}{q} + \left\lceil \frac{p - r}{q} \right\rceil.\]Hence, the right-hand side of $\eqref{eq:jeaiii fixed-length}$ can be written as